Agency v Compliance in Education

... or why AI *Can* Improve Undergraduate Education, But Won't Just Yet

Will AI Improve Undergraduate Economics Education?

“At the start of my graduate studies, the Journal of Economic Perspectives was a brand new journal and the Internet didn’t exist. Over time, there has been an explosion of unstructured content available for students eager to jump in. Blogs popped up, Twitter and X feature many top economists willing to engage with the public and Substack features many academic economists writing subtle pieces. Undergraduate teachers can find high quality material produced on many reputable websites ranging from the World Bank, VoxEU, and many Think tanks. In recent months, I have experimented with loading many interesting readings to a shared Google LM Notebook website and encouraging my students to ask the AI for summaries about these writings and to ask their own questions”

The title of the paper that this excerpt has been taken from is “Will AI Improve Undergraduate Economics Education?”. The author is Matthew Kahn. There are many reasons to read this paper: it is short, succinct, and a good read being chief among them. The fact that it has been written with Grok’s assistance is another. My chief reason for writing about this paper is because I like the careful phrasing of the title1.

But Why That Particular Title?

Here are some alternative titles for the same paper:

Can AI Improve Undergraduate Economics Education?

How can AI Help Improve The Way Undergraduates Acquire An Economics Education?

I would argue that there are two good reasons for not going with either of these titles.

We’re Already There, We Just Don’t Know It Yet

First, sections 3,4,5,6 and 7 in the paper are effectively an answer to the first question. AI absolutely can (and to a limited extent already is) improving undergraduate economics education. Matthew Kahn discusses this extensively through each of the sections I have mentioned above, and if you can find the time, please go through them in detail. In case you cannot, here are the section titles:

Integrating AI into Econ 101

AI Infused Intermediate Micro and Macro and Econometrics

Incorporating AI in Field Classes

Independent Research and Research Assistant Opportunities

Research Assistant Opportunities in our AI Era

Education’s Emperor Problem

Second, section 10 is as good an answer as any I have read for the second question:

“For far too long, students have been choosing majors in the dark—picking “prestigious” fields without really knowing what the degree will do for them, while universities have been able to hide behind vague reputations and opaque classrooms. Parents write enormous checks with almost no idea what they’re buying, employers wonder if the diploma still means anything, and everyone quietly suspects a lot of the game is just expensive signaling.

AI changes that. Cheap, frequent, AI-proctored assessments and virtual tutors suddenly make effort and mastery visible in real time. Professors discover whether students are actually learning the material. Parents can peek at meaningful progress dashboards instead of just getting billing statements. Employers can ask for verifiable records of real skills instead of trusting a transcript that could have been gamed.

When effort is easily observed, Deans can write optimal contracts. Will Deans (who often embrace horizontal equity considerations) reallocate funds to those departments that adapt to the AI challenge by producing a better product? Universities are non-profits. What do the Deans maximize? If they seek to maximize the expected present discounted value of graduate earnings then Economics Departments who infuse AI in their curriculum will prosper.”

Economists have their own shorthand for talking about these problems. We refer to them as asymmetry of information problems, or sometimes we will talk about principal-agent problems. But you can also, if you prefer, call this the “Emperor-Has-No-Clothes” problem.

Because here is the harsh unvarnished truth: parents absolutely do have an idea of what they’re buying with an enormous check. They’re buying the degree. Employers absolutely know that the diploma means something, and they also know that it doesn’t mean a good education. They know this because they’ve been through the same system themselves not all that long ago, and they know things haven’t changed much since they graduated. Everyone doesn’t “quietly suspect” that a lot of the game is just expensive signaling. They know it is just expensive signaling. But hey, why rock the boat?

That question isn’t meant as a rhetorical flourish. Why, indeed, should you be rocking the boat?

The Boat is Already Rocking

As things stand, universities have perfected over decades2 their workflows to be what they are today. Some of this is because it is economically efficient, some of it is because that’s what the market has desired in the past, and some of it is because of the need to comply with regulations. But within those pressures, quite naturally, universities have evolved into a system that has become thoroughly entrenched. There has been no pressing need to change. Why? Because the culture we live in today has our current form of pretending to dispense an education perfected to a finely honed performative art. As a society, we have applied just the right amount of veneer to those four odd-years that students spend in undergraduate learning to make it seem as if Learning Is Happening. More importantly, we have settled into a workflow where awarding the precious degree, and the granting of the even more precious mark-sheet, is all that matters.

Students, given this workflow for acquiring a degree (as opposed to an education), naturally seek to minimize effort while doing so. That’s not a comment on them, you and I did the exact same thing when we were in college, and we do it even today in our jobs. Minimizing effort to acquire something isn’t being lazy, it is being rational. Is that “something” worth acquiring in the first place, and are there better ways to acquire the true underlying thing?

These are difficult questions to answer. Battling the system as it is is more than enough work, why bother going through the fight of changing it?

It is because ceteris is not quite paribus3 anymore.

Creative Destruction

In the conclusion of the paper, Khan has these two paragraphs:

“The 2025 Nobel Prize was awarded to three economists for their work on how technological innovation drives sustained economic growth. Our own core field faces the AI innovation shock. How will we as individual educators and economics departments respond to this challenge? In this essay, I have sketched out my own perspective and I plan to crowd source my paper to see how people respond. When Creative Destruction4 comes home to our daily life, how do we respond?

Our adaptation task would be simpler if our consumers (our students) were time consistent! At age 20, undergraduates often prioritize immediate gratification—seeking courses with minimal effort, high grades, and entertaining delivery—to balance academics with social life, internships, and extracurriculars. Yet, at age 40, alumni frequently reflect on what truly prepared them for career success: not easy electives, but skills in causal reasoning, handling uncertainty, and adapting to technological shifts.5”

AI is a technology shock to education. AI is the technology shock to end all other technology shocks, but that is a story for another day. For now, for the purposes of this essay, it is enough to understand that AI is very much a “creative destruction” force. We already have the tools that are capable of dispensing a much more customized, personalized, easily-monitored, more-rigorously-measured education. There is no technological constraint that stops us from being able to do so. Again, sections 3,4,5,6 and 7 in the paper give you glimpses of how this could be done, and there are many people who are working on advancing early research in this area6.

The constraint in improving the dispensing of education isn’t technological. Quite the other way around. AI has helped unlock a much better way to dispense education. The problem is that there is a lack of demand. And that’s down to culture.

AI Is Pushing Us Towards A Coasean Singularity

There is interesting research about this now available, and I have covered how a reduction in transaction costs might affect higher education previously. Briefly put, AI will reduce search costs for many economic transactions, leading to more efficient markets. Firms will become more efficient in terms of judging labor inputs, and firms will be able to get much more done with a much more skeletal task-force. Effort monitoring will become a lot better, and this matters for us because this can be true in the case of education as well. Why? Because AI can observe a student’s progress much better than can a professor or a college7.

Think of traditional firms or colleges as being the equivalent of an internal combustion engine (ICE). These engines have many moving parts, don’t work as efficiently, and they need the many parts of the engine to move in perfect synchronicity with each other. A good ICE has many parts, all of which work a fair bit with each other, need frequent replacement, and call for regular maintenance and upkeep. There is a lot of friction.

AI-first firms or colleges, on the other hand, are like electric motor engines. They have hardly any moving parts, work much more efficiently, and do not need anywhere near the same level of regular maintenance and upkeep. There is hardly any friction.

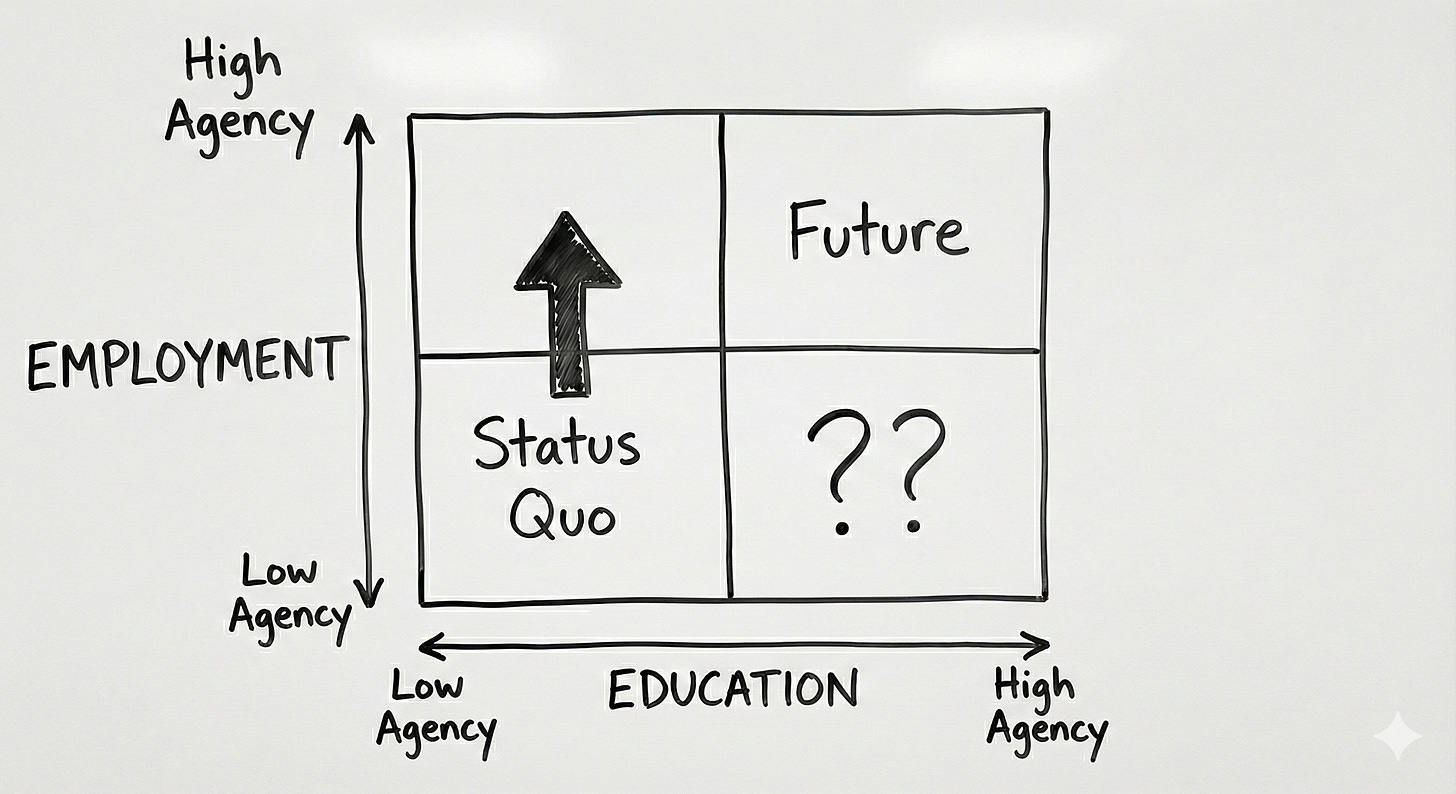

The ICE world (which is our old world with no AI in it) calls for compliance, and our current university system is excellent at producing reasonably high quality employees with high compliance. The electric motor world (the new world, with AI very much in it) calls for agency, and our current university system is horrible at producing high quality employees with high agency. Educational institutions do not reward a student for finishing a course in two weeks, and nor do they appreciate a student looking at a course syllabus for an entire degree and saying, “Well, with AI’s help, I can master this to anybody’s satisfaction in only two years as opposed to four”. Education today has a Two Minute Mile problem.

Where Are We Headed?

How realistic is it to assume that we (and that’s all of us, as a society) are headed towards a Coasean Singularity? I am not asking if we will reach or attain that singularity. I am asking how realistic is it to assume that we are headed in that direction. My day job is already providing some important updates in that direction, and I hope to be able to share some of our findings with you here soon. I suspect most adults reading this have either already experienced moves in this direction in their firms or businesses, and I suspect many more will experience lurches in this direction in 2026.

Firms and businesses respond to market pressures, so one should expect this move to happen in response to market based incentives, assuming AI progress continues. Educational institutions respond to cultural pressures at least as much as they do to labor market dynamics (and possibly more), and only partially to market based dynamics. Whether the movement will happen at all or not, and whether it will happen as quickly as it does in the case of market facing firms and businesses, is the key question facing educational institutions today.

If I’m right about the vertical axis, the question is about whether, and if, current educational institutions will be able to adapt and move. This will depend upon our culture’s ability (and speed) to adapt to our new reality, and raise our cultural demand for high agency education. Fighting against this will be our cultural inertia, guided by our entirely understandable cultural preference for maintaining the status quo.

To the extent that our educational institutions fail to adapt quickly, there is going to be a growing disconnect between the new firms in this new economy, and the old educational institutions from our old-but-oh-so-familiar-and-comfortable economy. Will resistance win out over revolution, or will the gravitational pull of the new economy be too powerful to resist?

The answer I favor isn’t one that is acceptable to the current culture of education. But it is going to be increasingly inevitable, and in some ways already is. Watching this fight will be exciting, entertaining and best of all, educational.

Enjoy it.

I write this essay from an Indian point of view. The degree to which my arguments apply in other contexts will obviously vary.

And in some places, centuries.

Ceteris Paribus is a phrase that means “All other things being held constant”.

From Google: “Creative destruction, a term popularized by economist Joseph Schumpeter, describes the “perennial gale” of capitalism where new innovations constantly destroy old industries, products, and practices, making way for new, more efficient ones, driving long-term economic growth and progress, even as it causes job losses and industry decline in the short term”

I cannot help but point out that we as a society have done an excellent job of telling all twenty year olds, every year, that the point is to acquire the degree, not the education. Is it any wonder that their time preferences are not consistent?

NotebookLM, covered in different places in Kahn’s paper, can already do a lot of the heavy lifting. Why NotebookLM has not yet been baked into Google Classroom is a mystery, but surely it is but a matter of time.

Or, in the jargon of the economist, AI can reduce asymmetry of information problems. This is related to footnote #3 above.