When AI Eats Transaction Costs

Notes from a Coasean Campus

Friction in Real Life

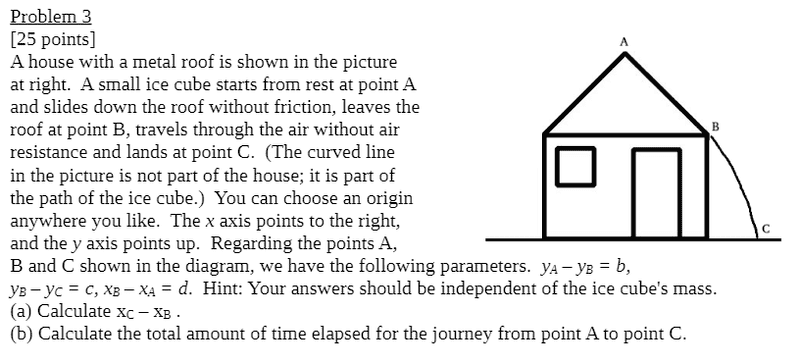

I spent most of the second half of the year 1999 staring balefully at stuff like this:

I was preparing for the JEE, you see. Or at any rate, that’s what my folks thought I was doing. But that’s a story for another day. The reason I begin with this uncherished, unloved memory is because of the third line in the problem. That small ice-cube, you will note, slides down “without friction”.

Now, in real life, this never happens.

There is always friction.

And not just in physics, but in economics too.

This simple idea - that friction exists in economics - is going to take us on a very long tour through many different fields.

Friction in Economics

Economists like to begin their journey of understanding the world by building simple models. Very simple models. We might imagine, for example, only two people in an imaginary economy. We will further imagine that these two people trade only two goods with each other. And from this very simple set-up, we grow many different important and powerful ideas in economics.

Is this realistic? Of course not! But it has the advantage of being simple, and tractable. Abstraction lets us focus on the essentials

But there must come a point when we take these toy models out to meet reality. And in reality, all of those abstractions that we waved away come back in full force, and us economists have to figure out a way to deal with them.

What kind of abstractions have come back to haunt our pretty little toy model?

Think about a very simple transaction, like buying a T-shirt. In the real world, there are literally thousands of people willing to sell you a T-shirt. Whom should you buy that T-shirt from? This vendor here, or that one there? So it turns out that it’s not just the price of the T-shirt, there are other costs that you have to pay as well. Say hello to search costs.

No self-respecting Indian will ever agree to buy a T-shirt at the stated price in an offline, informal market. Why, the seller might well be offended if you decide to just accept the opening quote. Negotiations are very much par for the course. But these take time, are a delicate dance, and don’t always work out well for both parties. These are transaction costs.

The seller of the T-shirt will know more about the T-shirt being sold than will you, the buyer. The seller knows about the quality of the T-shirt (will the colors “run” during the first wash?), the provenance of the T-shirt (where has it been made), the quality of the stitching, and so on and so forth. The buyer and the seller don’t have the same amount or quality of knowledge about the good being sold. Economists call these asymmetry of information problems.

Say the seller is so confident about the quality of the product that they guarantee you that it will last for six months, no matter what. So confident are they, in fact, that they have a no questions asked refund guarantee. Does this make it more likely that you will not take good care of the product you’ve purchased? This is the problem of moral hazard.

You may celebrate the purchase of the T-shirt by buying a glass of sugarcane juice from the seller next door. Does the sugarcane juice seller owe the T-shirt seller a cut from the sales proceeds? No of course not. Sure, the sugarcane juice sale happened only because the T-shirt sale happened, but this is what economists call an externality, or an unintended consequence1.

That’s not a comprehensive list, but it is a fairly good one to start with. And the thing you need to realize is that these problems occur in many, many different transactions, with varying degrees of intensity.

Not that I meant to go all meta on you, but we just went through a toy model ourselves! Search costs, transaction costs, asymmetry of information problems, moral hazard problems and externalities can and do occur in many different contexts, and not just the toy model scenario of one buyer buying one T-shirt.

And so the point is that in much the same way that the ice-cube sliding down the roof sans friction ain’t realistic, so also with all of economics.

There’s friction everywhere.

How To Solve A Problem Like Friction

These friction causing things are a problem for economics. Why are they a problem? Because just like in physics, friction slows things down. These frictions raise transaction prices, and therefore deter trades from happening. Either the buyer or the seller (or both) may think that price is not good enough, and may therefore choose to walk away from the deal. That means fewer trades, and us economists, we no likey when people no trade. Trade, in our view, trumps no trade.

So how do we make all of these frictions go away?

Well, there are three ways:

Reduce ‘em.

Subsidize ‘em.

Build your way around ‘em.

Reducing them means coming up with innovative ways to mitigate their impact. Governments and/or firms can do this. Zomato and LinkedIn both help reduce information asymmetry problems, for example2.

Subsidizing them means reducing the price of the trade by having the government pay part of the price. This works in reverse too, in the sense that a negative subsidy is simply taxation3.

That third bit - building your way around ‘em - is one of the things that institutions do. A guy called Ronald Coase wrote an entire paper called “The Nature of the Firm”, in which he explained how firms are just a way to internalize transaction costs4.

Technology, It Is A-Changin’

The thing is, all of these solutions assume that technology doesn’t change. That is, it assumes that we will never be able to come up with technologies that don’t just solve these problems, they make sure these problems don’t crop up in the first place.

Go read the footnote that ends the previous section. How does that footnote square with what Sam is saying in this clip? How can one person come up with a billion dollar firm without “having to constantly go out into the market to find someone new for every single tiny job”. How can a firm simply obliterate search and transaction costs5?

It is certainly true that firms were an institutional structure. Firms reduced search costs by hiring full time employees. But when you have an AI agent who is fast becoming capable of doing some of the tasks that your human employees would have done, then the search and transaction costs start going down.

What does such a world look like?

Imagine A World (With No Transaction Costs)

The inspiration for the essay you’re reading comes from a much longer essay written by Seb Krier. You can read it here.

There is a lot to unpack in that essay, and I haven’t finished processing it entirely. There are some really interesting points in there, and there are some points that cause me deep disquiet. But that’s just all the more reason for you to read the essay! I’ll share here just the concluding paragraph, to give you an idea of the scale and the scope of the essay:

The vision presented here shifts the locus of governance from centralized coercion to decentralized negotiation. AGI agents can help us create a vastly more efficient, accountable, and adaptable society. There is no need to centralize all the labs into a government monopoly, nor should we just accelerate aimlessly and do away with the state. And unlike solving alignment for a singular, centralized AGI (where failure is catastrophic), the distributed model of millions of user-agent relationships creates a massive parallel experiment. It is a system that learns, adapts, and continuously aligns itself over time, allowing us to build a society that is both more free and more coordinated than anything that has come before.

As I said, this is too much for me to process right now, although I do plan to spend a lot of time doing just that over the next few days. Can we narrow down our focus to only a single slice of such a society? I have no idea what a world without transaction costs will look like, and I am completely lost about what path we will take to reach that world from the world we inhabit currently. But I do find it possible to imagine what college will look like in such a world.

Imagine a College (With No Transaction Costs)

Ask yourself this question: was your college able to offer you all of the courses you wanted to learn? The obvious and painful answer to this question is “Heck no!” for almost all Indians, and I probably did not need to qualify by saying “almost”. If you wanted to study economics, accounting, marketing, the history of music, physics and a course on sound engineering in order to start the world’s most awesome sound recording studio - well, you couldn’t.

This is not just because of how hopeless our education system is (although trust you me, there is no one who will be more sympathetic than me if you happen to have this opinion). Part of the reason this happens is because of transaction costs.

It is expensive for the college to go and transact with would be profs for abstruse courses. Good profs are difficult to find for even the more popular courses, and they’re all but impossible to find for courses less taken. Once you find them, they have to be in the same city, they have to be free to teach, and they have to be ok with whatever fees you offer to pay them. The chance of all of these things happening is next to zero.

But I’d urge you to go one level deeper. College itself exists because it is too expensive for you to do this yourself! Why couldn’t you go out and hunt down these professors and get a DIY degree of sorts? Because it would be even more expensive for you to do this all by yourself, for one.

Second, you would then have to do the second job that colleges do in India. You’d have to go out and convince folks that you had actually learnt. The college degree is important because it acts as a proxy for your quality. When you put the fourth and the eighteenth letters of the alphabet in front of your name, people think you know stuff. When you put a double shot of the ninth letter followed by the twentieth after your name, people know you know stuff. And convincing people that you know what you’re talking about without those things is possible, but it just takes longer.

Plus, studying alone is lonely. So is drinking alone, and hanging out alone. Finding friends is tricky, and college does that for you too! So college can be seen as an institution that minimizes transaction costs associated with:

Learning

Convincing people and firms you know your stuff

Finding out cool people to hang out with

That is, college is a bundle that minimizes transaction costs6.

And for many years - centuries, axshually - this worked out just fine for everybody concerned. Students, profs, and the labor market all were ok with this arrangement, because disturbing the status quo was more trouble than it was worth.

Goodhart’s Law ran amok, inevitably. A degree was supposed to be the measure of what one had learnt, but when it became the target, it very quickly stopped being a good measure. This became such a big problem that us economists decided to give it a brand new name7.

But now we have AI. How does AI help in reducing transaction costs associated with all of the functions of a college?

What is a better, cheaper way to discuss this blog post? Go find a good prof who will sit down and explain it to you at length, or do you want Gemini/Claude/ChatGPT to get to work? Does this apply to pretty much everything you’d like to learn8?

Increasingly, firms don’t care about your degree. If you are a fresh graduate, firms increasingly don’t care about you. If they do want to hire you, it becomes increasingly cheaper to find out how good you are using AI9. The degree already is, or will fast become, a very poor proxy of what you know. That was perhaps always the case, but firms no longer have any incentive to say that the emperor is wearing clothes10. (Also note AI also brings other frictions into play! AI will not just get more applications for the same job, as Derek points out in the essay I just linked to, but there might emerge competition about who learns more among students. Professors and mentors can drown in endless proposals for mentorship.)

But the third point is where I think college not just retains its old advantage, but it actually increases it. A college campus has the potential to not just remain a Schelling Point for young folks, but to become an even more important focal point. Remember, context is that which is scarce - and I’m betting on in person networking with like minded folks being a scarce good that we’ll be (very) willing to pay for.

A campus need not be a place you go to learn from, but a place you go to learn at. It (college) is a place where you meet interesting mentors, like minded peers, and professors who can teach you things that AI simply can’t (yet). It is not a place that issues a degree, or a place that decides what you should learn (and how).

The original meaning of the word “college” comes from the Latin word for partners. Partners in learning, as it were. And in a world with a significant reduction in transaction costs, college stands a chance of going back to its original roots11.

TMKK: Don’t Build Mechahorses

All of us are going to meet better, cheaper and faster version of the AI models we are currently using. This is going to happen in the weeks, months and years to come12. The party may or may not stop in times to come, but for the next two years or so, we’re going to have rapid advancements in AI.

We have two choices with these models:

Make existing workflows better

Reimagine workflows from the ground up

The challenge we will face is the same challenge that a fish faces when asked to define water. We just don’t think of college as a workflow. Ditto for offices and firms.

As search, bargaining, and verification costs begin to fall, my prediction is that some institutions will unbundle, at least partially. They will still (and they should!) sell what only they can supply. This could be trust, it could be curation, it could be status. I am betting that being around like minded peers will go up in value in such a world.

But in a couple of years, we will be well on the way to knowing if this thesis holds. My stance is that there will be a sustained drop in job posts requiring degrees. Hiring, to the extent that it happens, will happen via AI-enabled portfolio of work evaluations. There will be a meaningful shift of credits to modular providers. All this will happen even as (some) campuses will begin to excel at attention. Social capital will command a premium.

If this does not happen by, say, 2027 end, transaction costs were stickier than I thought. Either way, our work in academia remains the same: redesign education and hiring around an AI-first world for the delivery of education, and foster a healthy in-person learning atmosphere on campus. In a world where coordination is cheap but attention is scarce, the right question isn’t whether college survives—it’s what, precisely, you would still pay a campus to do.

And so also for the rest of the world.

This one was a positive externality, but there are also negative externalities, of course. A better example might be the Metro subway passing close by your house. That might make commuting by the metro a breeze for you (a positive externality), but it does make falling asleep at night rather difficult (a negative externality)

“That one restaurant outside an unfamiliar railway stations in the middle of nowhere at six in the morning. Is it ok to eat there or not?” Zomato solves this problem by showing you restaurant reviews.

”Should we recruit this guy for this role or not?” LinkedIn solves this problem by helping you understand what folks have to say about this person.

If there’s a steel mill that releases effluents into the river that kill the fish, thereby driving a fishery out of business, one can either tax the mill, or subsidize the fishery (or both).

Think of it like this: A business, or “firm,” exists because it’s a giant container for a lot of smaller tasks. Instead of having to constantly go out into the market to find someone new for every single tiny job, the firm just does it all inside. By doing this, the firm is “internalizing” the transaction costs that would otherwise be spent dealing with the outside market.

In practice, it won’t be quite as simple as obliterate. It’ll be, er, a gradient descent.

The Nature of the College is a paper Coase could have written, y’see

See this by Noah Smith, for example.

The point is not to answer who you would prefer to learn from. I’d prefer to drive a Ferrari instead of a Tata Zest from 2015.

Your portfolio of work can be scored by an AI model. You may be asked to do simple coding exercises set for you by an AI. Etc, etc.

I’m simplifying here (this is a blog post, after all). We won’t abruptly shift to this state of affairs, but I’m afraid I have no idea how the shift will take place. Gradually and then suddenly would be my bet, but that’s just a guess.

The number of things that could go wrong here is huge. Access to devices and the internet, caste and class issues, resistance by faculty (duh) and of course the gormint - these are all significant hurdles.

I think even the USA isn't ready to reimagine colleges yet. They have started increasing the social capital in their bundle already.

India will definitely have to be dragged kicking and screaming into the next era whenever it arrives because of how Indian society works. It won't be pretty for sure.