Transaction Costs and 25 Questions from Hollis Robbins

Introduction

As we discussed the other day, my thesis is that colleges can be thought of as a way to reduce transaction costs associated with education:

It is expensive for the college to go and transact with would be profs for abstruse courses. Good profs are difficult to find for even the more popular courses, and they’re all but impossible to find for courses less taken. Once you find them, they have to be in the same city, they have to be free to teach, and they have to be ok with whatever fees you offer to pay them. The chance of all of these things happening is next to zero.

But I’d urge you to go one level deeper. College itself exists because it is too expensive for you to do this yourself! Why couldn’t you go out and hunt down these professors and get a DIY degree of sorts? Because it would be even more expensive for you to do this all by yourself, for one.

Second, you would then have to do the second job that colleges do in India. You’d have to go out and convince folks that you had actually learnt. The college degree is important because it acts as a proxy for your quality. When you put the fourth and the eighteenth letters of the alphabet in front of your name, people think you know stuff. When you put a double shot of the ninth letter followed by the twentieth after your name, people know you know stuff. And convincing people that you know what you’re talking about without those things is possible, but it just takes longer.

Plus, studying alone is lonely. So is drinking alone, and hanging out alone. Finding friends is tricky, and college does that for you too! So college can be seen as an institution that minimizes transaction costs associated with:

Learning

Convincing people and firms you know your stuff

Finding out cool people to hang out withThat is, college is a bundle that minimizes transaction costs

Colleges are about more than this, sure. But this does capture a major chunk of why colleges exist, in my opinion.

Hollis Robbins asks twenty-five questions of higher-ed, and I wanted to see if we could fit her questions (and their answers) into my little framework.

What Is The Carnegie Unit?

Hollis Robbins’ post makes frequent mention of the Carnegie Unit, and in case you didn’t know what that means, here’s a quick explainer from Google:

Indian college students are likely to be much more familiar with “credit requirements”, and the Carnegie Unit is the granddaddy of this set-up. But what you should note with the Carnegie Unit is something much more interesting: seat-time is a proxy for learning.

The assumption is that if you spend x hours studying a particular subject, you will have mastered it. Validation takes place via tests, assignments etc, but the focus is on hours spent studying the subject as proxy for how well one should know it. As Hollis Robbins puts it:

Acceleration matters beyond classroom practice. Once learning velocity is systematically measured and institutionalized, the entire temporal organization of education collapses. Age-graded cohorts, semester schedules, and degree timelines are all based on the idea that learning happens at a predictable, standardized pace. Of course this was never true. But AI both enables and amplifies this variation.

What acceleration is she referring to? The fact that AI allows those so inclined to learn much faster than preset semester schedules and degree timelines. But as transaction costs eat away at the ability to find ways to learn well, and learn quicker via access to AI, not everybody will end up learning at the same rate.

The usual thing to do right now in a blog post such as this is to ask this question - “How do we solve this problem?”

But perhaps (at least in an Indian context), the better question to ask is this -

”Is anybody even thinking about this problem?”

Here’s the problem, explicitly stated:

In about three to four years, first year undergrad students will have grown up learning how to use AI tools to learn. When these students enter college, how should we think about what to teach them, how to teach them, and how to make sure that they’ve learnt?

What Does AI Change in Higher Ed, And With What Consequences?

The implicit assumption that you need to spend x hours per subject (and therefore y years in college) is what is known as time based credentialing. When the speed at which folks learn changes, this assumption no longer holds.

The reason the speed at which folks will learn will change is because AI solves for the transaction costs associated with finding good one-on-one tutors. These are going to be available in very short order (and you can make the case that they’re already here), and we see precious little evidence that colleges are changing in response to a change in the technology that underpins the delivery of quality education.

There are three legs to the stool of higher education: learning, credentialing and networking. The more learning unbundles itself from college, the more important it is to be able to provide credible credentialing, and credible networking. Otherwise, why would anybody choose to give (a lot of ) time and money towards the acquisition of a college degree?

This may be true the world over, but I cannot speak with any claims of expertise as regards higher education in other countries. In India, however, I do have some experience when it comes to teaching in higher education, and when it comes to higher education, there is a counter-intuitive truth that really matters.

There may be a missing middle when it comes to income classes in India, but there is no missing middle in India’s higher education. Quite the contrary, in fact - there are a very large number of colleges that fall “in the middle”. These colleges do not provide the best learning experience to begin with, at least relative to the very best educational institutions (that is why they’re in the middle).

So if AI is going to eat away at their ability to dispense learning, they’d best get better at credible credentialing and equally credible networking.

The 25 Questions

Hollis Robbins has 25 questions that university presidents should be asking their teams. Easily more than half, I would say, are about transaction costs in one way or the other.

It would be nice if folks in Indian academia did the exercise of answering some or all of them, and it would be even nicer if some students in Indian academia today decided to talk about this in class with their profs. In my opinion, it would be a great way to learn how to think about what is coming, applied specifically to higher education in India.

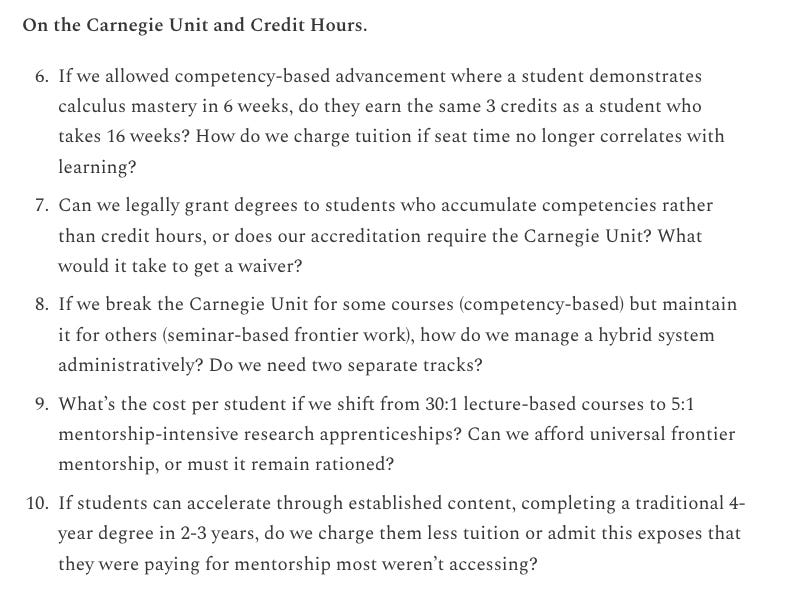

If you’re in higher ed in India, please spend some time going over these questions and thinking about them. The bee in my bonnet is the Transaction Cost bee, and I therefore found this section the most interesting:

Of particular interest was Q9. The Indian higher education system takes in a ever-higher number of students per year, and charges all of them more than the previous year’s cohort. A typical MBA class, for example, will be at least sixty students (and in my experience, could sometimes be twice that size). Other colleges will limit the number of seats per division to 60, but then increase the number of divisions. I’m teaching stats this year, and it’s 60:1, three times over. That is, each day, I teach three divisions, and there are sixty students in each class.

I assure you that I do not have the time for universal frontier mentorship for 180 students every semester. No one does. In terms of my framework, colleges already suck at the Starbucks leg of the college tool and this gets a little worse every year.

Tech-bros can (and should!) bring the technical expertise needed to solve this problem. But academia can and should bring the expertise - this is a problem where academia has metis, and academia should make good use of it.

If it is not to be the Carnegie Unit, what kind of pricing are we looking at, and how do we think about the pricing of Indian higher education in the years to come?

These are not easy questions to answer, and there is going to be a fair bit of experimentation that will (hopefully!) happen. Micro-payments for micro-credentials? Pay for access to just being in a learning atmosphere? Split the money you earn for completing research projects with your mentor? I honestly have no idea about what will work, but I hope with equal honesty that we see some experiments in the very near future.

The Most Important Question of Them All

Hollis Robbins saves the best for last:

Q25. In 10 years, when students can get personalized content mastery for free or cheap and arrive at college having completed what we currently teach in years 1-2, what exactly are we selling? Research apprenticeship? Network access? Credentials? Time to mature? What’s the honest answer?

My personal (and perhaps Utopian) answer to this question is “Research apprenticeship, network access and time to mature”. I would aspire to work towards creating a university where students get the chance to work on research apprenticeships. I would want students in such a university to meet regularly and often with folks who will increase their network, across many different domains. And I would want students to simply spend time living well and learning well while in college, because what could possibly be more important than that?

But hey, I’ve been dreaming about the death of the classroom (but not the university!) for a very long time, and inertia in academia is decidedly a canine of the fairer sex. Not only has it not happened yet, there are no signs that it will happen anytime soon.

But just because it hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean that it never will, and surely it is worth pondering on these questions, and coming up with your own frameworks about how to think about the future of higher education in India. So, please, do think about these questions, and especially the twenty-fifth one.

I’ll end with a paraphrasing of how Hollis Robbins ends her blogpost:

How likely is it that a four-year, time-based degree model will change significantly over the next ten years? What will/should replace it, and what are your thoughts about it?

Work with AI

Upload this piece into your AI tool of choice, and consider asking some or all of these questions during your chat with the tool:

How does the work of Williamson and/or Coase help me understand this blogpost better?

Who was Gary Becker, and why does his work on human capital matter here?

What is signaling, and how is the work of Caplan/Spence related to what we’re talking about here?

What is Bloom’s 2-Sigma problem, and how might AI solve this problem?

Does India’s NEP reduce or increase transaction costs?

How likely is it that firms will be able to develop cheap and efficient assessing systems? Is it likely that assessment will get unbundled from universities?

How likely is it that our personal assistants will act as our tutors? Will commoditized learning get unbundled from universities?

This is not an exhaustive list! Ask many more questions of this blog post!

The best readers are those who take an idea (or bundle of ideas) to the next level. This is a super smart piece and you are right to focus on transaction costs as your bee. Subscribed! (Your other pieces are excellent too.)

In India, since getting into a good college is mostly to get good jobs (it's mostly about the money), I think future of higher ed will depend on how the corporations decide to recruit people.

Top institutes are probably safe for now since they still provide a measure of status in society (signalling).

I probably envision something like competition for the top institutes intensifying but after the cut-off there will be a dramatic drop (power law) and people will just enrol in a convenient college and focus on learning skills by using AI if they can see that their college name won't matter as much when applying for good jobs.

This probably happens even now but it will definitely accelerate in the future.