Slow Gold

“She is old enough, and foreign enough, and intelligent enough, to understand that Fashion (which lesser women view as if it were Gravity) was merely an invention, a device. It was devised by Colbert as a way to neutralize those Frenchmen and Frenchwomen who, because of their wealth and independence, posed the greatest threat to the King.”

Quicksilver, by Neal Stephenson

Some months ago, Karthik Raghavan Ravi recommended that I read The Baroque Cycle trilogy by Neal Stephenson. I have been luxuriating in a slow read of the first book since, and it has been a thoroughly enjoyable experience. This post is not a book review, per se, but it does use the book as the spine of the post, as it were.

Quicksilver is not a book to be finished in a hurry. One should savor it in slow sips, delighting in the oddball discoveries you make along the way. Did you know, for example, that the Scottish word for the English phrase “water of life” is usquebaugh?

Or consider this delightful-little-but-etymologically-rich exchange:

“Those damned pirates have loaded so many cannon aboard, she rides far too low in the water, and so she’s got a great ugly Zog.”

“Is this meant to reassure me?”

“It is meant to answer your question.”

“Zog is Dutch for ‘wake,’ then?”

Dappa the linguist smiles yes. Half his teeth are white, the others made of gold. “And a much better word it is, because it comes from zuigen which means ‘to suck.’”Stephenson, Neal. Quicksilver (The Baroque Cycle Book 1) (p. 385). (Function). Kindle Edition.

There are many reasons to read this book, some of them of a More Serious Nature. But fans of etymology will get handsome returns on their investment. As indeed, will fans of trivia, as we shall see in this blogpost.

Back To That Quote About Fashion

I knew that the word fashion comes from facere, a word in Latin which means “to make, or to do”. “He fashioned a tool out of the rock” doesn’t sound wrong because of this etymological connection - you are saying that he made a tool out of the rock.

So when did fashion begin to mean what we think it means today? Thinking about that quote at the top of this post is a good way to start to answer this question. And boy is it a fascinating tale!

Let’s begin with the ngram:

Now, as a fiction writer, Stephenson has taken a fair few liberties in the telling of this somewhat historical tale. But what makes it an extremely informative read is the ability to chat with an LLM about the book while you are reading it. This helps you figure out what actually happened, what somewhat happened, and what never happened at all while you are plowing your way through the world he has created. But it also allows you to go off on fascinating tangents, should you choose to.1

So let’s go explorin’!

Who is Colbert?

That would be Jean-Baptiste Colbert, King Louis the XIV’s First Minister of State. Fans of mercantilism2 may remember Colbertism. That’s the fellow we are talking about.

If you’re familiar with that saying about taxation, about it consisting of so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest number of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing, then that too is Colbert.

And so most students of public finance will know of Colbert, and what he was up to back then, in terms of policymaking. But this quote wasn’t interesting because of the what. Most economics students memorize in excruciating detail the what.

“Colbert’s central principle was that the wealth and the economy of France should serve the state. Drawing on the ideas of mercantilism, he believed state intervention was needed to secure the largest part of limited resources. To accumulate gold, a country always had to sell more goods abroad than it bought. Colbert sought to build a French economy that sold abroad and bought domestically.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colbertism

It was interesting because it was hinting at the how.

Status Games

Elsewhere in the book, there is a description of life as a noble in France back then:

It is plain to see that Louis keeps the powerful of France on a short leash here, and that they have nothing to do but gamble when the King is absent and ape his words and actions when he is present.

Stephenson, Neal. Quicksilver (The Baroque Cycle Book 1) (p. 457). (Function). Kindle Edition.

Long time readers of this blog know that one of my favorite questions to ask is “What are you optimizing for?”. And the lesson you need to learn is that the “powerful of France” were optimizing for gaining the approval of the King.

Why were they optimizing for gaining the approval of the King? Because that was the only game in town. They had nothing to do but gamble when the game wasn’t being played, and game being played was kissing the King’s posterior. The only way you stood a chance of getting pensions, offices, military commands or legal favors was by currying favor with him, and the King let it be known that aping him was a good way to curry favor with him.

And so you had to talk like him, you had to eat like him, and above all, you had to dress like him. And dressing like him, it turns out, wasn’t easy. Or cheap!

While raw materials for textiles – mainly silk and cotton yarn – had to be imported, under finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert and Louis XIV France developed into a centre of cloth manufacturing. In fact, the strict quality controls practised by the Grande Fabrique, a type of guild, turned Lyon into the world’s foremost silk-weaving hub. In the mid-17th century, multiple, systematic changes in fabric design per year were introduced as part of a protectionist economic policy that sought to maximise exports and minimise imports. In addition, a court calendar was launched at Versailles, prescribing which items of clothing or accessories should be worn at what point in the year. There were two main consequences of this. The first was a market in which the timing of the sale became crucial. The second was that silk producers both served and fuelled demand for new designs, colours and grades of cloth with a variety and virtuosity that had never been seen before.

We’re All Playing Games

A chat with Gemini and NotebookLM about the topic led me to a conversation about the works of Norbert Elias. One of his theses is that you are best off thinking of Versailles as a stock exchange, where the good being traded isn’t commercial paper, but “the value of the people present in each other’s opinion”. Said value could be acquired only through close observation and replication of the elaborate rituals (and fashions) of the King himself.

Fans of Quicksilver will note the delicious symmetry of this analogy with the actual stock market described at Amsterdam, but if you haven’t read the book, some elaboration is in order.

The book moves through many different arcs, of which there are four prominent ones. One takes place inside Versailles, as we have learnt just now, and is the game of status and political intrigue. Another takes place in the financial markets of Amsterdam, where modern finance is being born. A third takes places in London, where Newton, Hooke and company get up to weird and wonderful experiments in the physical realm, and even more weird and wonderful experiments in the mental one.

The book examines the sociology of all three societies (and other things in other societies besides), and it is especially pleasing to think of the Versailles arc in financial terms. It is these hidden connections making themselves manifest that reading along with an LLM unlocks, and at a rate that is far faster than was possible earlier.

That one throwaway quote about fashion allowed me to have so many different and intertwined conversations with AI, and allowed me to learn more (and faster) than I would have otherwise.

In the book itself, learning happens via travel, both of people and information. But both happen at much slower rates, of course. And when inhabitants of one world learn how other parts of the world function (or don’t), it causes not a little disquiet.

But that last bit, it must be said, remains the same, across space and time:

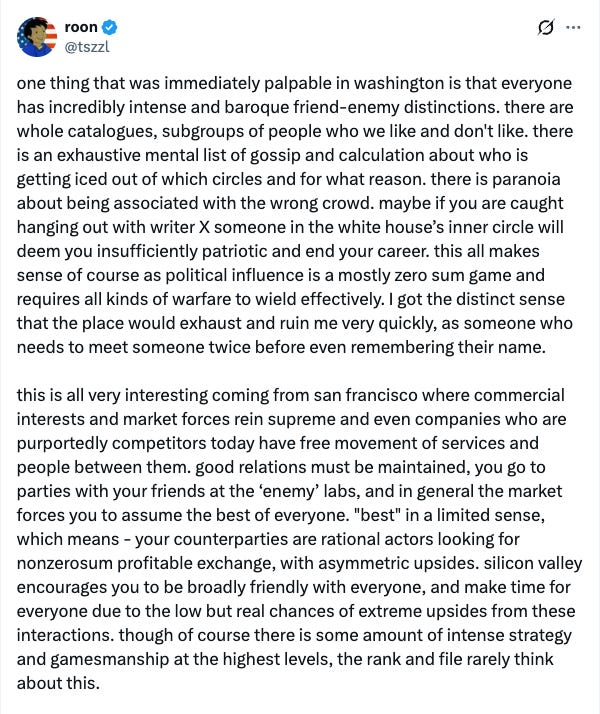

Roon ends his tweet with a quote from Francis Fukuyama:

“The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.”

You should read Quicksilver because it helps you understand that it is not so much the end of history we should be worried about as an endless repetition of it. Although perhaps the real lesson that Neal Stephenson and Norbert Elias are trying to teach us is that our inner loops have been playing the same games all along.

Back in the world that Quicksilver describes, you had no choice but to play the game of the place that you were born in: Versailles, Paris or London. Only the protagonists of this fictional account had the ability to move their pieces across all of the chessboards.

But in today’s world, everybody can choose which game they wish to play. But learning the nature of each game, the prize on offer at the end, and how those games intersect with each other is a lifelong process. That process becomes much more enjoyable, and a little more decipherable, by reading a book such as Quicksilver.

And now I cannot wait to start Book Two!

And why wouldn’t you, eh?

The study of it, not the practice