On Thinking About Growth

I listened to a fascinating conversation between Dan Wang and Tyler Cowen yesterday evening. Dan Wang is the author of the excellent Breakneck (my review here), and I was curious to see what Tyler would choose to, er, interrogate him about.1

Soon after, I happened to read this post by Tyler. I couldn’t help but make connections between the two, and I wanted to explore those connections in this post.

How To Think About Macroeconomics

Back when I used to teach introductory economics, I would tell students that the study of macroeconomics is the study of three basic questions:

What does the world look like?

Why does it look the way it does?

What can we do to make the world better?2

The reason I bring that up over here is because it is not just a good way to think about learning macroeconomics - it is also a good way to understand how to “place” what book you’re reading.

Breakneck is a book you should read to get a better sense of one of the answers to Question 2: why does the world look the way it does? Dan Wang is giving his answer to the question of why two particular slices of the world (the USA and China) look the way they do. His answer in the book is that this is so because the USA today is a mostly lawyerly society, while China today is a mostly engineering society.3

I love thinking about the many, many answers that are possible in response to Question 2, and so I loved thinking about Breakneck, including thinking about the obvious question: “If the US is about lawyers and China is about engineers, then what is India about?”.

Which brings me to one of the many reasons you should listen to Conversations With Tyler. If the conversation happens to be about something that you think you know, you often learn of a way to slice better.

In my review, I had written admiringly about how good Dan Wang was with his analytical cleaving skills, and how thinking about the world in this particular way (lawyers v engineers to think about US/China) was a very useful and novel framework.

Listening to the podcast helps you realize that Tyler has a better way to think about the framework. Useful and novel, sure, the first half of the podcast is saying. But is it the best way of thinking about the issue that the book is talking about?

Is the lawyer v engineer framing the best way to answer the question “Why does the world look the way it does?”

I think Tyler is telling us that Dan Wang’s answer doesn’t take us 98.5% of the way there.

How Do Economists Think About Question 2?

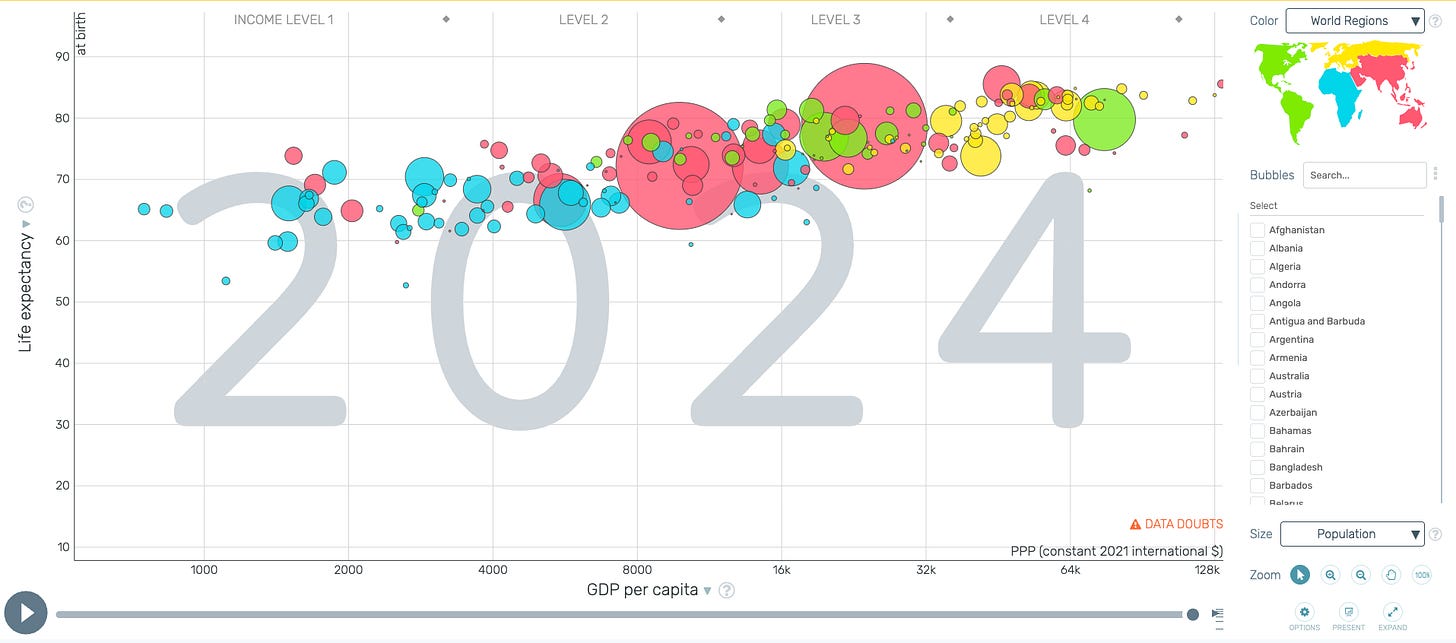

Question 2 is one of the most important questions you can think about in macroeconomics. One of the most obvious things to say about the world we live in is that some countries are rich, and some countries are poor. We should be minding the gap:

We have income on the horizontal axis, we have life expectancy on the vertical axis. The color of the bubble indicates the region, while the the size of the bubble indicates population. Gapminder is a great way to answer Question 1, by the way.

Obtaining an answer to Question 1 demands the existence of Question 2. Because the longer you stare at a chart such as this one, the more urgently you begin to wonder about it. Yes, it is true that all the African nations are towards the left bottom, but what explains the variation within them? Some red bubbles (Asia) are towards the extreme right, while others are towards the extreme left. Why? And so on, and so forth. It is hard, as they say, to stop thinking about this once you start.

Economics students faithfully work their way up a particular chain of thought when they learn about how to think about Question 2. They learn about Rosenstein-Rodan, Harrod-Domar, Solow and then Romer.4

That is very, very far from being an exhaustive list. But most economists would agree that it is a good list in that it gives you the major stops along the way of how economists have thought about the issue.

Tyler’s Blogpost

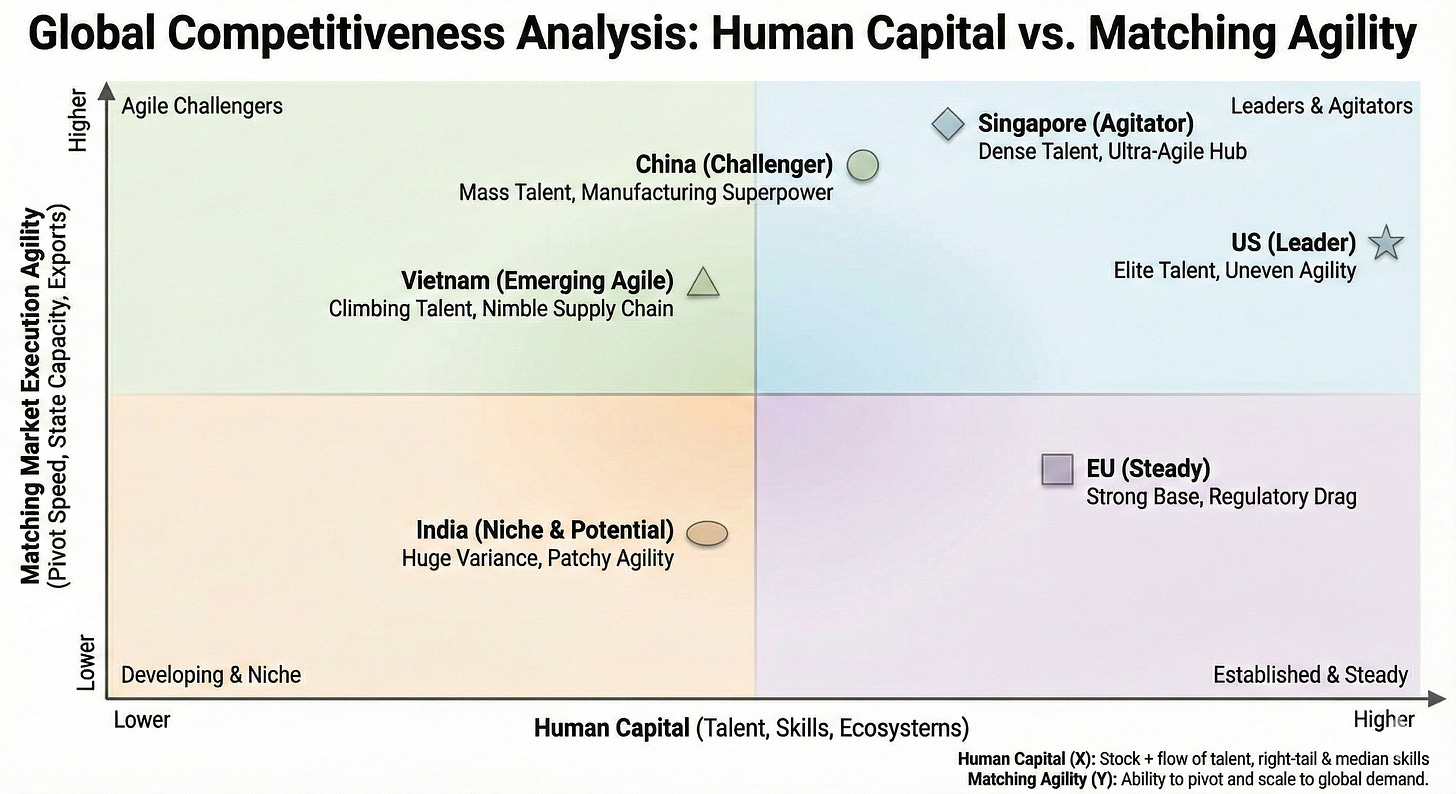

Tyler says all of those approaches are fine, but his take on the issue is slightly different. His own answer to the question of where growth is going to come from is the following:

Human capital: How much active, ambitious talent is there? And how high are the averages and medians?

Matching market demands: Are you geared up to produce what the market really wants, export markets or otherwise?

To put it in non-economist terms, Tyler says that successful countries are elephants who can dance. You absolutely have to be elephantine in terms of human capital.5 And perhaps just as importantly, that great mass of human capital also has to be able to pivot fairly rapidly (that’s point #2).

There’s much more nuance there, but that’s my first layer of understanding of Tyler’s post.

Is Being Insufficiently Lawyerly the Actual Chinese Vice?

The title of this section is one of the questions Tyler asks Dan Wang in their conversation. I see this question as Tyler asking the question “Why is your lawyer v engineer framing better than my human capital v matching market agility framing?”. My read of this part of the conversation is that Dan’s answer is that a more lawyerly society would have never let something like the excesses of the one-child policy happen (or the kind of social engineering that we saw during China’s Covid-19 lockdowns). I suspect Tyler is in complete agreement about the diagnosis of the problem - he’s asking if more lawyers is the solution.6

So what is Tyler’s answer to the question of what is the actual Chinese vice, then? Tyler is the obvious person to ask, but my answer to this question, using Tyler’s framework, is to say “not good enough human capital”. Or of the two things that Tyler’s framework hinges upon, human capital matters more than the ability to pivot, and the US is just simply better at human capital than China.

Human capital in this case is really at least two different things: the “mass” of collective human capital, but also how well it is able to network among itself. And while China may have some chance at getting within shouting distance of America in the case of the former, it will always fall short at getting that mass of human capital to network well. That’s the real Chinese vice.

Two Additional Points

You could also apply Tyler’s growth framework to firms (as we already implicitly did for IBM) and individuals. But in both cases, the framework doesn’t copy over perfectly. Networks and mentors matter for personal growth, and culture and risk-taking matters for firms. But still, it is a great starting point. In fact, consider Tyler’s answer to Dan’s question towards the end of the conversation:

”If there’s a new thing it seems I can learn, or should learn, I’ll want to do it. You could call that a grand strategy, like to become an information trillionaire. It’s a grand strategy. Different things pop up.”

That’s pretty close to #1 and #2 in Tyler’s model!What are the limitations of the growth framework that Tyler suggests? I’d say the variation within #1 (human capital), and how each society handles it, and its long term implications. We’re looking at a real time live experiment in the USA as we speak!

Dan Wang, during this podcast: “You’ve started this extraordinarily successful podcast, which I’ve always felt we should maybe rectify the name, sir. Rather than having this be called Conversations with Tyler, maybe we should call this Interrogations by Tyler”

And I used to love adding this line: “Understanding what we mean by the words “we” and “better” is 99% of the battle!”

There’s more to the book than that, and there’s more to the issue than that

Please ask your LLM of choice to explain that sentence, if you like.

And apologies for stretching the analogy too far, but you also need great networks between many, many elephants

Or, if you prefer, Dean Ball’s take is applicable here: create snowmass on the mountain top, and let the water flow, rather than impose a scheme of top-down integration. Create better human capital, and let that human capital figure out how to solve the problem, in other words.

Yes I nodded at this: "I loved thinking about Breakneck, including thinking about the obvious question: “If the US is about lawyers and China is about engineers, then what is India about?”

Isn’t it astonishing that the American “experiment “ hasn’t been copied ? Maybe the wrong questions are being asked…