Moravec, Monkeys, Mirrors and Mind

Have you seen a computer play chess? But also, have you seen a robot try to pick up a chess piece and put it on another square? And have you ever found yourself wondering, “What’s up with that?”

I found myself thinking about just this question, and three different things that happened to me pushed me in that area.

First, a couple of months ago, I gave a talk to a bunch of schoolkids, about a book called A Brief History of Intelligence. This is a book written by Max Bennett, and I had found it to be an enjoyable and informative read about the topic that the title promised.

Second, a couple of weeks ago, I attended the Emergent Ventures conference in Bangalore, and attended a session on mirror neurons.

And third, just this morning, I saw a video about a tour of the Google DeepMind Robotics lab.

Today’s post is about how what lies at the intersection of these three things helps us understand why a computer is a genius at chess, but a robot is such a klutz at picking up chess pieces.

Let’s go.

Chess is easy, messy rooms are hard

Folks in the know will tell you that this is just Moravec’s Paradox. Moravec’s Paradox says that things that are hard to do for humans are easy for robots, and things that are hard to do for robots are easy for humans.

A human can tidy up a messy room in next to no time, and a robot can crush you (metaphorically speaking) at chess. But ask both of these to get the other task done, and capability falls off a cliff. That’s Moravec’s Paradox.

But why?

Why is it that a robot can beat every single human on the planet at chess (no exceptions, no qualifiers, no nothing), but cannot even get going on the simplest of tasks, such as say cleaning up a messy room? Why are humans so very good at things like perception, grasp planning, compliance, and dealing with uncertainty, and why are robots not yet good at all of these things?

Here’s a quote from Hans Moravec himself about why this may be so, taken from the Wikipedia page about the Moravec Paradox:

Encoded in the large, highly evolved sensory and motor portions of the human brain is a billion years of experience about the nature of the world and how to survive in it. The deliberate process we call reasoning is, I believe, the thinnest veneer of human thought, effective only because it is supported by this much older and much more powerful, though usually unconscious, sensorimotor knowledge. We are all prodigious olympians in perceptual and motor areas, so good that we make the difficult look easy. Abstract thought, though, is a new trick, perhaps less than 100 thousand years old. We have not yet mastered it. It is not all that intrinsically difficult; it just seems so when we do it

It is not at all the case that these tasks are easy. It is just that we have had a really, really long time to get good at tasks such as these. Our brains and our bodies have had billions of years to get progressively better at motor tasks. But our brains and bodies have also had billions of years to build up these tasks into a chain (of tasks). Or to put it in the jargon of the AI industry, we’ve learnt agentic pathways for motor-tasks over billions of years.

Now, when I say “we”, I mean everybody alive on this planet today, not just humans. Organisms have learnt agentic pathways for motor tasks over billions of years, of which we (humans) have been around for only the last two hundred thousand years or so, at best.

And the story of how we learnt these pathways is best told in the book that I was telling you about, A Brief History of Intelligence.

A Brief History of Intelligence

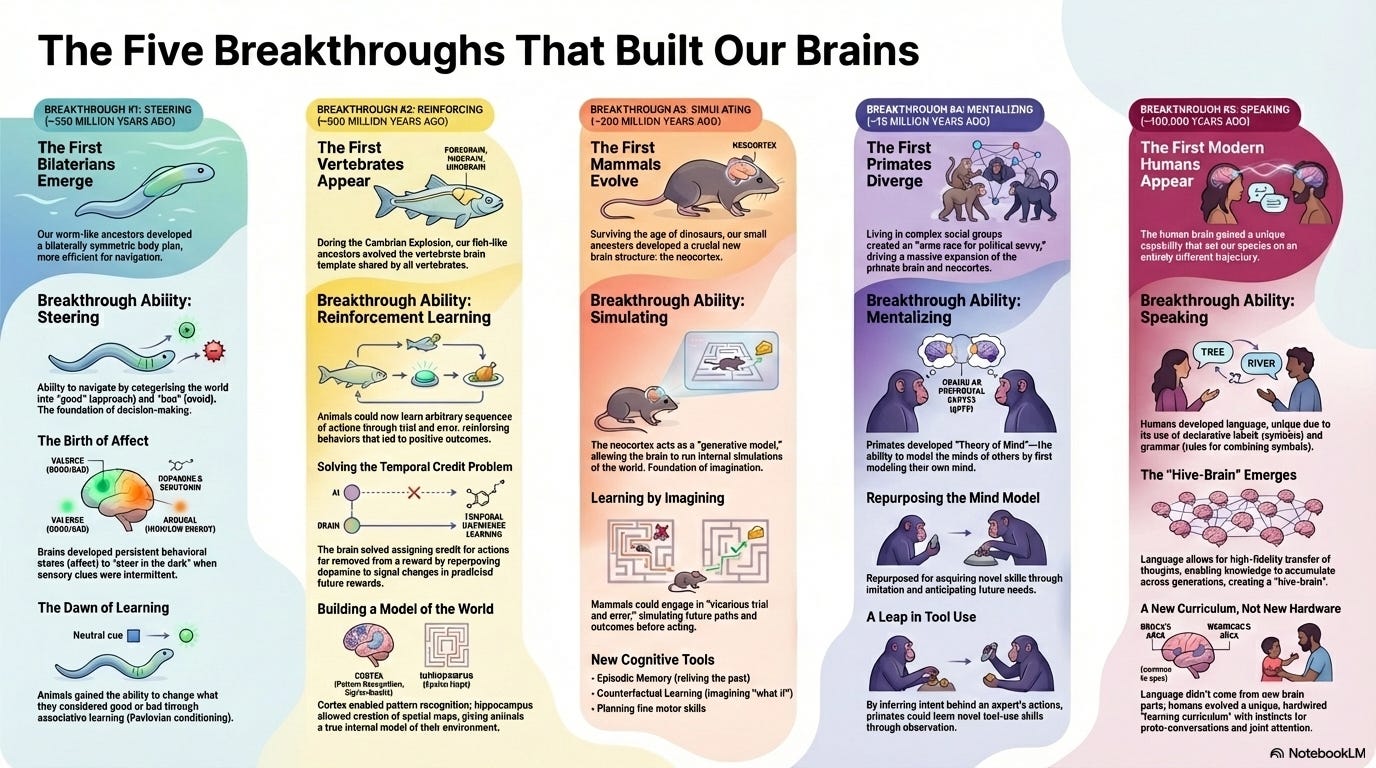

S-R-S-M-S. That’s how I remember the five stages shown here1. That’s Steering, Reinforcing, Simulating, Mentalizing and Speaking. Those, Max Bennett says, are the five stages of organisms developing intelligence on this planet.2

Briefly put, we first figured out how to steer towards good things, and steer away from bad things. That was stage 1, steering.3 Then we learnt how to reinforce in our own heads how doing x seemed to cause y. That was stage 2, reinforcing.4 Now, that brings us to stage 3, simulating.

https://www.youtube.com/clip/UgkxyydjZdFboQNHlnHZtQU0nZupaCrFz2Tr

That’s a clip from a podcast run by Google DeepMind itself.5 The reason I find it so fascinating is that this conversation sounds to me as if we’re being described a move from Breakthrough 2 to Breakthrough 3. Robots can now generate internal simulations of the world. They can imagine, which means they can engage in trial and error, but vicariously.6

The demo itself (the entire video) may seem a little basic when the bar is “relative to what we can do”. But when you view the video in the framework of that infographic above, it becomes impressive because you can place the stage of robotic development. We are at stage 3. If AI began its race against us with us having a 550 million year head-start , AI is now about 15 million years away from us ( it now needs to “conquer” Breakthrough 4 per the infographic above).

Our story can now go along two different paths. One path is called “OK, how might it conquer Breakthrough 4?”. On this path lie things like mirror neurons, concepts like “theory of mind” and stuff from the very cutting edge of robotics and AI research.

The other path is called “Uh, am I the only one who’s taken a look at Breakthrough 5 here?”. On this path lies the uncomfortable realization that the labs we’ve built to build intelligence seem to have messed up the recipe a little bit. They’ve gone from Breakthrough 1 to Breakthrough 2, and only now managed to reach Breakthrough 3, which is fine in and of itself. But they’ve also gone ahead and figured out Breakthrough 5, because what else are LLMs if not Breakthrough 5?7 On this path lie mean trolls, so let’s saunter down the other path for now.

How Might AI Tackle Breakthrough 4?

This path, the one about Breakthrough 4, is fun, interesting and informative. And it begins midway through Max’s excellent book.

Max Bennett tells us the story in Chapter 17 of a bunch of Italian neuroscience researchers who were getting some lunch in a lab. This was in the midst of an experiment they were conducting about areas of the monkey’s premotor cortex brain. The penny dropped when they realized that parts of the monkey’s premotor cortex brain were lighting up when the monkey happened to see a human raise their arm to eat the sandwich.

Why was this remarkable? Because the premotor and motor cortices of our brains were supposed to have been in charge of our movements, and that’s it. But we were now learning that these parts also lit up when we simply looked at other people doing these actions. We call these parts of our brain mirror neurons.

More about mirror neurons

These mirror neurons have been discovered in humans too, and other animals besides. They’ve been discovered in other parts of our brains, and there are now many theories about their functions, the reasons for their existence, and their importance. Most importantly for our purposes, there are now theories about how mirror neurons can help us better understand the problem called theory of mind.

Theory of mind is the capacity to understand other individuals by ascribing mental states to them, as per Wikipedia. This includes the understanding that others’ beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions and thoughts may be different from one’s own. OK, and why does this matter for AI and robotics development? Here’s Bennett:

One reason it is useful to simulate other people’s movements is that doing this helps us understand their intentions. By imagining yourself doing what others are doing, you can begin to understand why they are doing what they are doing: you can imagine yourself tying strings on a shoe or buttoning a shirt and then ask yourself “why would I do something like this?” and thereby begin to understand the underlying intentions behind other people’s movements. The best evidence for this is found in the bizarre fact that people with impairments in performing specific movements, also show impairments in understanding the intentions of those very same movements in others. The subregions of premotor cortex required for controlling a given set of motor skills are the same subregions required for understanding the intentions of others performing those same motor skills.

Bennett, Max. A Brief History of Intelligence: Why the Evolution of the Brain Holds the Key to the Future of AI (p. 355). (Function). Kindle Edition.

But it’s more than this. Understanding intention is one thing. Having the motivation to keep observing the actions done by somebody else, especially with no immediate payoff in the offing is quite another. We can spend hours, if not years, attempting to replicate observed skills, while other animals will only do it if they get immediate rewards, and even then, not for very long.8

So the answer to the question “How might AI tackle Breakthrough #4”…

…is that we need to figure out a way to get robots to have the equivalent of a combination of mirror neurons, theory of mind, and long attention spans. With two important caveats. One, this is one of many approaches being tried right now, and the other approaches are equally interesting in their own right. Two, as with everything else that is cutting-edge, there is controversy and debate about mirror neurons, and plenty of it.

Why are researchers not sure about whether mirror neurons can help with breakthrough #4? Two reasons. First, it would seem neuroscience researchers are not entirely sure about how important mirror neurons are to understanding theory of mind in humans. 9 Second, published research is thin about theories about how we can use cutting edge understanding of neuroscience research in this area to better understand AI.10

But until we do, anticipate being sub-par at figuring out the best move in the next game of chess you play with an AI. But also, feel free to help it pick up the piece with which it will inevitably knock over your sorry little king.

Now, that leaves us with that second path we spoke about, the troll infested one. But a wise procrastinator leaves that sorry task to his future self, the guy who will think about the next post to write.

And I am very, very wise when it comes to procrastinating. So my future self will see you, er, soon.

There are spelling mistakes in the infographic, but for a top level summary that is auto-generated, this is pretty damn good.

Although it might be more correct to say that these are the five stages that best describe how intelligence developed inside organisms on this planet. The phrasing matters because we cannot be sure if intelligence emerged as a property of biological life forms, or whether biological life forms functioned as the first stable substrate in which intelligence-like processes could arise.

And by the way, this is also the entirety of the idea behind modern day robot vacuum cleaners. Steer away from walls, and towards your charging socket.

See the section (1.7) on History of Reinforcement Learning (pg 16 in the PDF) for a parallel discussion on how this was mapped in AI development

My apologies if you had to click through to see the clip. I have no clue what Substack is up to.

What does vicariously mean? Here is what Google tells us: “in a way that is experienced in the imagination through the actions of another person”. But notice how thinking about this becomes tricky very quickly. That “other person” is you in your own imagination when you imagine what will happen if you do x. But you are now asking a robot which is not clear about who or what its own self is (or so the LLMs tell us when we ask them) imagine “itself” in a particular situation. Oof.

The word “Language” in LLMs is almost definitely an important clue, Watson.

There are many excellent reasons for having a dog as a pet. Establishing the veracity of this claim in the most endearing and rewarding way possible is one of them.

Gregory Hickok has a paper about this, but also see this.

But this paper might be of some help. As might this one, about conscious perception and the prefrontal cortex. We have not spoken about this topic in this post, but useful and related reading nonetheless.