IABIED: Why You Should Read This Book

IABIED stands for “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.”

In case you live under a magical rock that allows nothing except my blog to get through, the “it” refers to superintelligent AI. Or ASI. Or whatever you choose to call it. The point the book makes is that if anybody builds it, all of us die.

Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares have written the book in order to pass on this message to as many people as possible. If you don’t have the time to read the book, or choose not to read it, you will still know what the book is about. Because the content, the message and the warning in and throughout the book happens to be the same as the title of the book.

And just in case you missed it, I’ll repeat it here, because it really matters to the authors that you get the message:

If anyone builds it, everyone dies.

There are two very good reviews of the book that I recommend you read. One is by TheZvi, and the other is by Scott Alexander.

This post isn’t only a review. It is me explaining to you why I think they’re wrong. But that does not mean I think their book is in any way bad, or not worth reading!

Usually, people write book reviews to share their opinion of the book, and readers read these reviews in order to get a sense of whether they should spend their time and money on the book in question. If that is the reason you are reading this post, I’ll save you some time and give you these two points right away.

The book is written as simply as possible, and the central idea in the book and its implications and its defense are given in plain simple English. It is a short, simple but very disturbing read.

You absolutely should read this book. Decide for yourself if you agree with the idea in the book, that is up to you. But in the year 2025, there is no way you cannot be acquainted with the ideas in the book. You owe it to yourself.

For the record, I disagree with the idea in the book. I do not think it is a guarantee that if anyone builds superintelligent AI, everyone will die. The future is unknown, and it lies ahead of us. For that reason alone, I cannot bring myself to assert something this important so unequivocally. TheZvi says that the only change he’d make is that he’d add in the word ‘probably’. I agree, but that does then raise the obvious question: what is your estimate for the probability?

My own estimate is about twenty percent. I think there is a one in five chance that we will be wiped off the face of this planet by 2040. Why 2040? Given current rates of improvement, I do not think that it will take longer than that for us to find out, one way or the other.

By the end of the post, you will have learnt my reasons for saying that there is a one in five chance of total extinction. But more than my own estimate, what I hope you take away from this post is an informed way to come up with your own estimate. That estimate will help you decide what you should be doing about the key message in IABIED.

That’s my argument for why you should be reading both the book, and the rest of this (very long) blog post.

Let’s get started.

Why Are Y&S So Worried, Anyway?

They are worried because superintelligent AI is a cause for worry. This, in turn, raises three related questions:

What is superintelligent AI?

What are the dangers of building superintelligent AI?

Who are the folks who do serious work in this area?

The reason those first two questions are important is because you only have an incentive to learn the answer to the third question if you understand and appreciate the answers to the first two. We will start, therefore, with those two questions, and I’ll share some useful resources re: the third question towards the end of this post.

What is superintelligent AI?

In the words of the authors of the book we are talking about in today’s post, this is superintelligence:

A mind much more capable than any human at almost every sort of steering and prediction problem.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer; Soares, Nate. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI (p. 26). (Function). Kindle Edition.

All the way back in 1965, the mathematician I.J.Good1 defined it like this:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.

Good, Irving John. "Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine." In Advances in computers, vol. 6, pp. 31-88. Elsevier, 1966.

The second definition, although older, is actually better in my opinion. The reason it is better is because it spells out one of the consequences of a ‘super’intelligent or ‘ultra’intelligent machine.

What consequence? Read the last sentence from I.J. Good’s definition, and ask yourself a question. If it really is an ultraintelligent machine, will it choose to tell us humans how to keep it under control? If it chooses to do so, would that be an act of intelligence? Ask yourself the same question about, well, yourself. If you were an ultraintelligent entity, would you choose to tell the other, less intelligent beings around you how to “keep you under control”? Would that be an intelligent act on your part?

Well, now that you are thinking not-fun thoughts, try this on for size: what will a superintelligent machine do with all of its intelligence? One of the things it can do is design another machine that is even more intelligent2, leading to an “intelligence explosion”. The implication in I.J. Good’s definition was spelt out - the intelligence of man would be left far behind.

Yudkowsky and Soares go further than that. At the end of the chapter in which they define superintelligence in their book, they ask what will happen when earth sees machines that are as intelligent (or more) than not just any single human, but are more intelligent than all of humanity put together.

That is superintelligent AI - an intelligence that is better than all of us put together.

What are the dangers of building superintelligent AI?

The whole point of getting on this journey to building out AI was to get better at doing so, right? Then why the worry?

This is both a fair and an obvious question. Ever since we figured out how to build computers, the point has been to try and build better, faster and cheaper computers. Similarly, and on what must surely be an entirely related note, ever since we figured out how to build artificial intelligence, the point seems to have been to try and build better, faster and cheaper intelligence.

And, you might continue, I can get being worried about jobs and all that. But survival itself? Really?

Yudkowsky and Soares say that the reason survival itself will be a concern is because of wants. Specifically, they say that one needs to ask a simple question. If you succeed in building a superintelligent AI, what will such a superintelligence want?

Y&S say that a superintelligent AI will probably not want humans to be around:

Imagine, now, a machine superintelligence that somehow has the ability to get what it wants. (Shortly, we’ll cover the means and the opportunity; for now, we’ll just focus on the motive.) If you look through its eyes, the situation probably looks like this:

Humanity is an inconvenience to you. For example, if you allow humans to run around unchecked, they could set off their nuclear bombs. Maybe that wouldn’t destroy you if you’d taken halfway decent precautions like burying your automated infrastructure underground. But the radioactivity would still make it harder to build precise electronics on Earth. So you’d rather the hominids not have nukes.

And if humanity had already built you, they could build another superintelligence, if left alone and free and still in possession of their toys. Those other superintelligences might be actual threats. Even if the end result would be a treaty and coordination rather than war, why split the galaxy with a rival superintelligence if you don’t have to? That means only getting half as much stuff.

So you are, as a machine superintelligence, looking for a way to relieve the humans of their more dangerous toys, the nuclear weapons and the computers. That is a motive, just by itself.Yudkowsky, Eliezer; Soares, Nate. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI (pp. 89-90). (Function). Kindle Edition. (Emphasis added)

I wish they hadn’t said “probably” and “might”. Or at least had given footnotes that explain what probabilities to assign in both of these cases. There is a link to additional material at the end of each chapter, and the resources associated with this chapter do throw this up. It is worth reading the whole thing, but the key paragraph, to me is this one:

“If what I really, truly wanted was simple explanations for my observations, and I didn’t care about human stuff, how could I get as much of what I wanted as possible, as cheaply as possible?”

I’m fine with the assumption that a superintelligent AI will:

Want the most parsimonious explanations for its observations.

Not care about human stuff

But I am not quite clear about why the AI will always want, for eternity, to pursue an overarching goal of efficiency. Why is that axiomatic? Now, you might turn back and say that hey, aren’t you saying the same thing yourself in Pt. 1?

I’d say no, I am not, because it is fair to expect that when it comes to expending resources in order to build a worldview, you’d like to be as efficient as possible. But why should figuring out what to do with the obtained worldview have to have efficiency as a optimizing variable3?

Why do we need to assume that a superintelligence’s preferences will always have efficiency as an overarching meta-preference? Sure, you might say “Because that is our definition of intelligence/rationality”. I will even agree with you - except to point out that you’re focusing on the phrase “definition of intelligence/rationality”, and I’m focusing on the word “our”.

Preferences are endogenous in the evolution of intelligence, no? Acquiring more intelligence should also imply the ability to have evolved preferences, and why should we assume the worst about never being able to update a purely mechanistic view of the importance of efficiency? Goal misgeneralization is a thing, and you should read about it. You should also read about deceptive alignment. You should think through the implications, but at the very least, you should also be thinking “You just can’t tell, and maybe bad outcomes aren’t a guarantee?”

How do you think about the answer to such a question? How do you claim to be able to predict what something-that-doesn’t-yet-exist will want?

One way to answer this question is to ask what the earliest and first forms of intelligence wanted. Trace out the story of how that intelligence evolved, and how its wants changed over time, and think about what that might imply for what a superintelligence might want.

Well, what did the earliest forms of intelligence want?

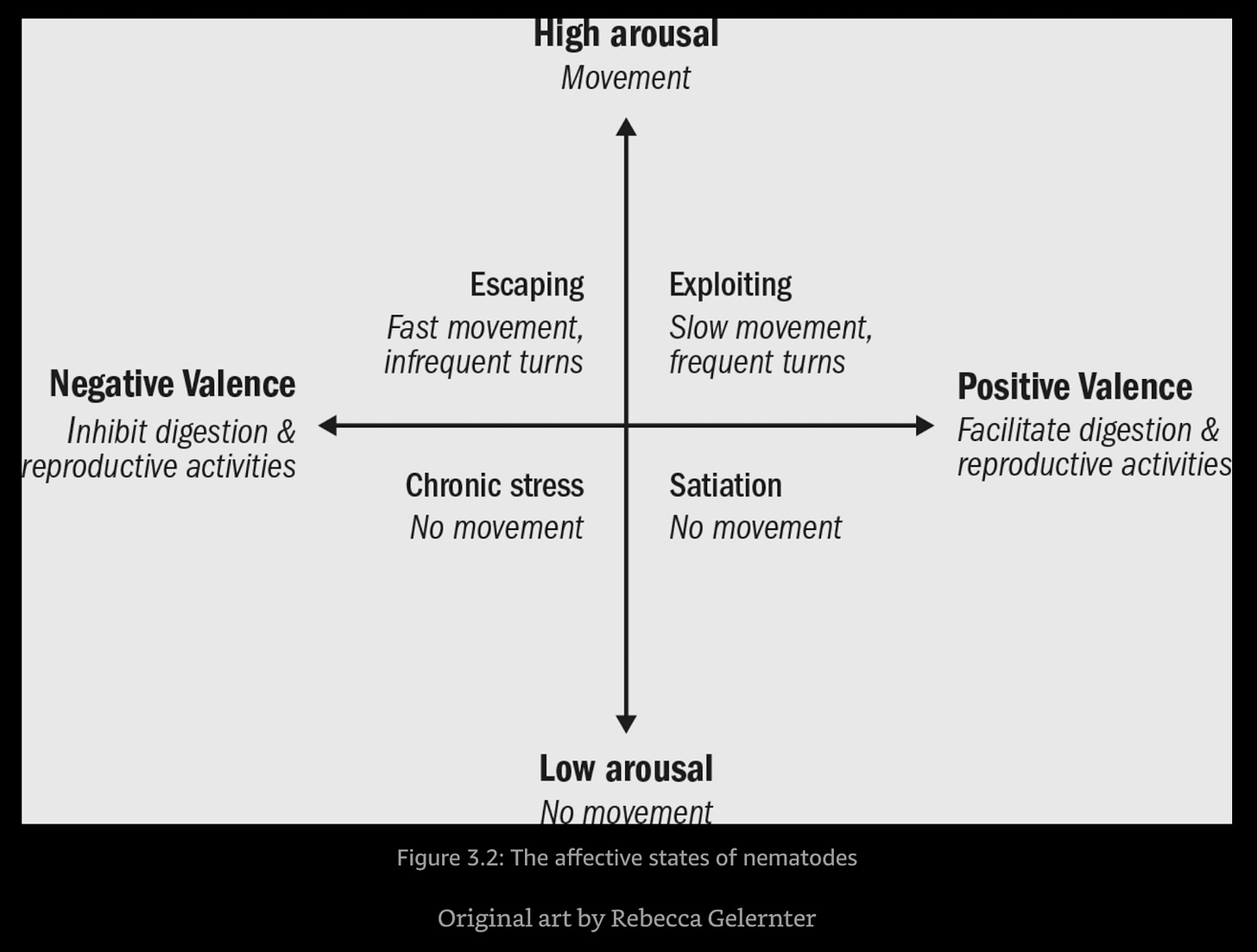

Max Bennett has the answer in a nice little book called A Brief History of Intelligence: Why the Evolution of the Brain Holds the Key to the Future of AI. The earliest form of biological intelligences (nematodes), were able to move towards places that facilitated digestion and reproduction (positive valence), and away from places that hindered these two processes (negative valence). They were likelier to move when in a state of hunger ( high arousal), and less likely to move when highly satiated (low arousal).

Yudkowsky and Soares say that much the same framework applies in the case of artificial intelligence. Intelligence, they say, is about two types of work - predicting the world, and steering it. “Prediction” is guessing what you will experience before you have experienced it (predicting that your tongue will be scalded if you drink extremely hot tea, for example). “Steering” is about choosing a set of actions that lead you to some chosen outcome (choosing to stay clear of that mug of tea until it becomes a bit cooler, for example).

This simple idea, of combining predicting and steering, applied at mind-boggling scale, can take us surprisingly far. It can take us, for example, from nematodes (600 million years ago) to ChatGPT-5. Because both the nematode and ChatGPT-5 are making use of the same ideas: prediction, and steering.

But of course, it is a bit more complicated than that. Today’s models are also taught to understand what skills are available to them, and to keep at a problem until these models succeed:

Since 2024, AI companies have been turning LLMs into so-called “reasoning models,” which we mentioned briefly in Chapter 2. Roughly speaking, an LLM produces many different attempts to think through, say, a math problem until one of those attempts succeeds. Then gradient descent is applied to make the model more likely to think out loud that way. Then it’s given a second problem. A third. A fourth. A hundredth. What does this train for? Separate skills like “figure out what actions are available” (an ability to predict how a problem works) and “don’t give up before all options are exhausted” (an ability to steer through a problem), which together combine into a general mental tool that works on many different problems. It trains for dozens of separate prediction and steering skills, all of which contribute to an AI behaving like it really wants to succeed.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer; Soares, Nate. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI (pp. 49-50). (Function). Kindle Edition. (Emphasis added)

OK, But What Do Modern AIs want?

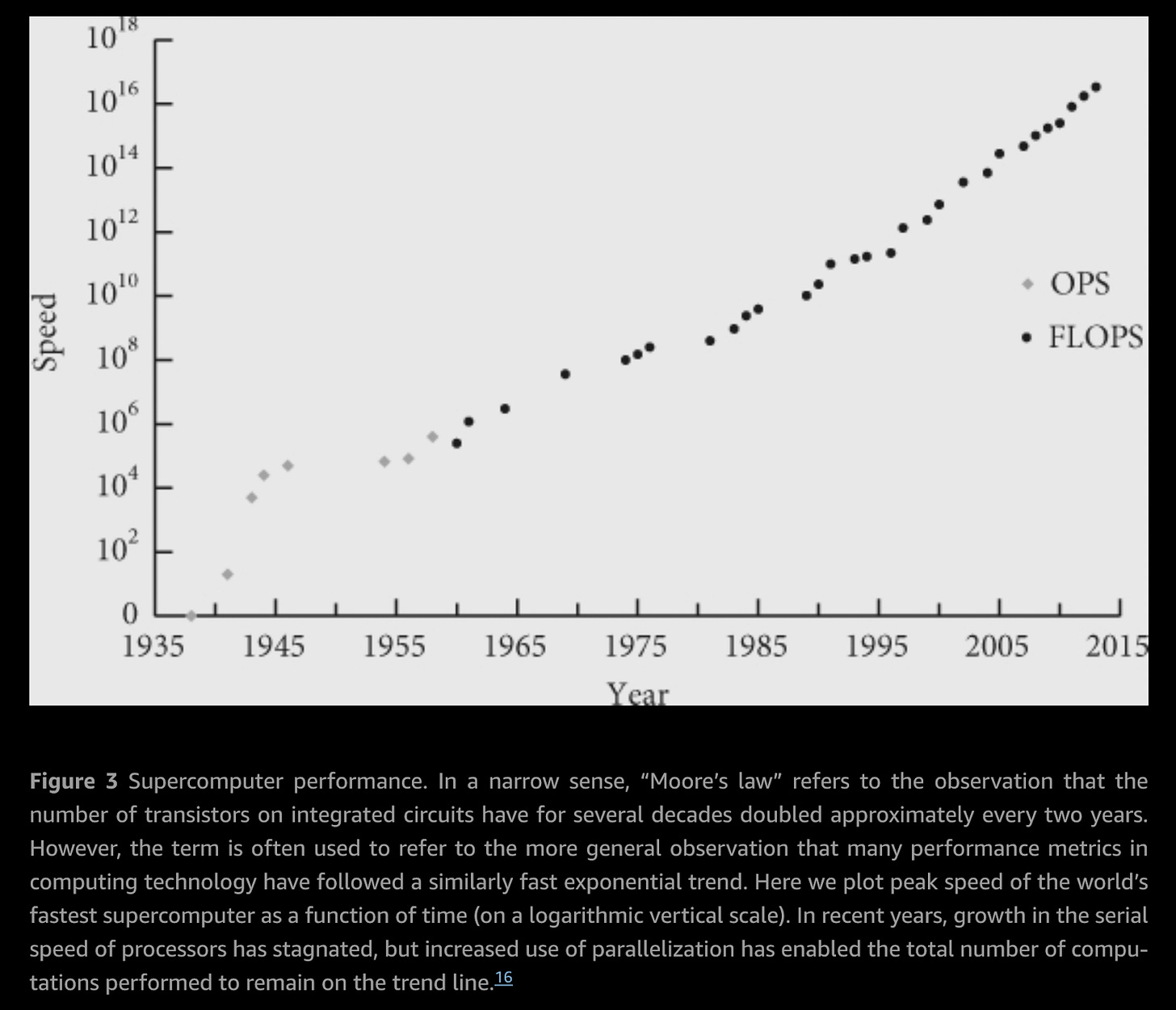

We’ve given modern AI a helluva lot of computing power, taught it how to steer and predict, and then taught it to really, really want to successfully finish a task we’ve given it. How much is a helluva lot of computing power?

That chart is from a book called Superintelligence, written by a guy called Nick Bostrom. That chart might not look all that impressive until you realize that the vertical axis is a log scale. Supercomputers have been getting a 100 times better every decade for the last eight decades. That trend hasn’t petered out, and note that this chart ends in 2015 (which is when that book was written).

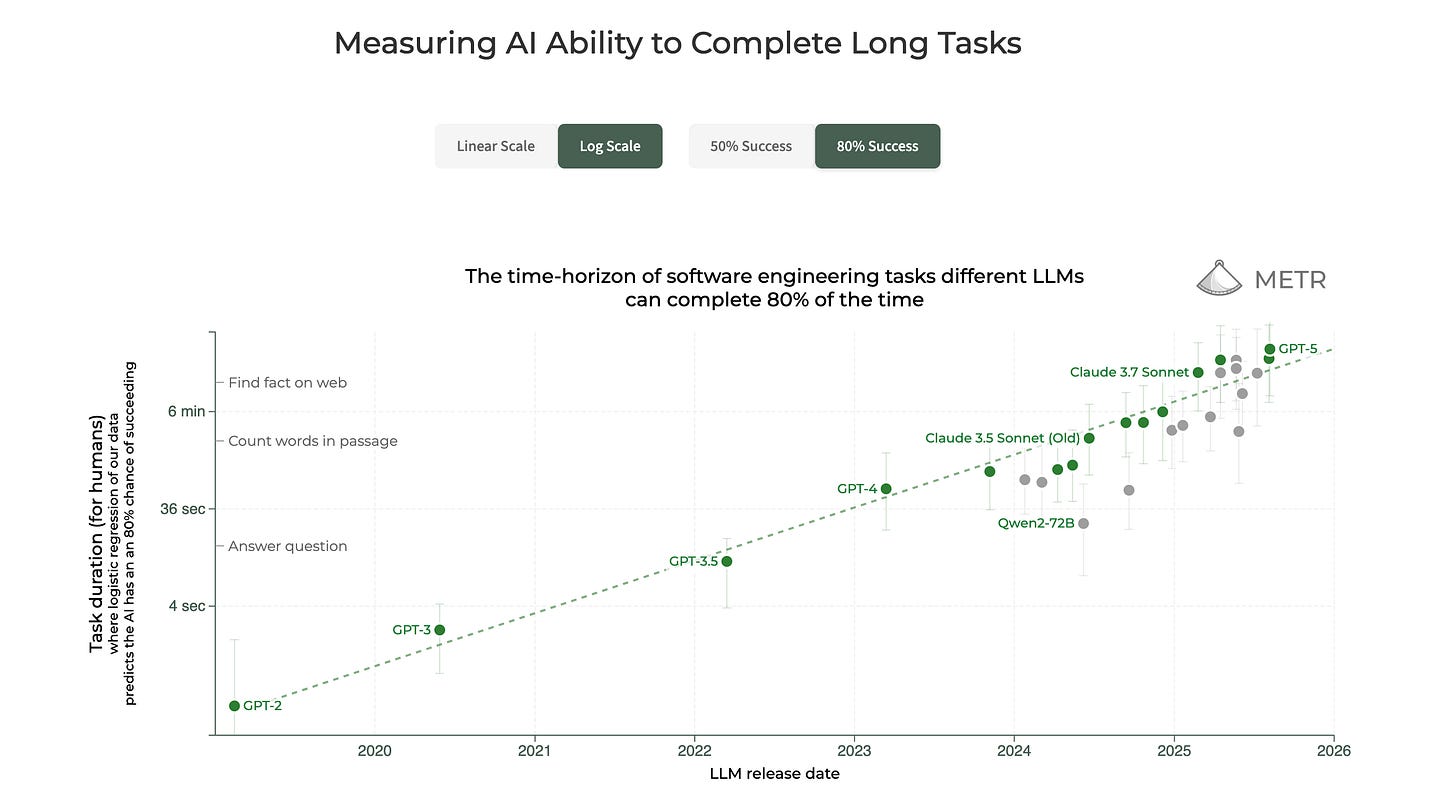

But of course, not only has computing power kept right on going, but the capabilities of the AI models we have been developing since at least 2020 has also been increasing. How quickly, you ask?

So the computing power behind these models gets a hundred times better every ten years, and the models themselves get about ten times better every eighteen months or so (roughly speaking)… and we seem to be upping the rate of improvement. So, if you are a first year undergrad student today, you need to have a clear idea of what your competition is likely to be like four years from now. The only consolation is that pretty much everybody is going to be like a fresh graduate student in comparison to whatever comes along four years from now.

But anyways, now we know that these models and the computational power behind them is getting a lot better, very quickly. We can go back to discussing what this section was about: what will such creatures “want”?

This is one of the areas where Yudkowsky and Soares are on shaky ground, as I discussed above. In Chapter 4 (“You Don’t Get What You Train For”), they talk about the difficulty of being able to predict what intelligence will want as it evolves. Imagine that you looked at the earth back when apes were roaming around, and we hadn’t yet made an appearance. You might predict that as these apes evolved, and acquired more intelligence, they would evolve to eat food that was full of nutrition and energy.

Did that happen?

No.

We evolved to love ice-cream.

Similarly, they say, we have no way of predicting what preferences these alien minds that we’re growing inside of labs will have. And in the next chapter, they state that these alien minds will:

Not find us useful (just the same way that we didn’t find horses useful once we invented the motorcar)

Not want to trade with us (all those cute theories about comparative advantage are out of the window, they state)

Just not need us to be around (not even for menial tasks, eventually)

Not even want us as pets

Simply won’t leave us alone

They don’t say it quite this way, but in effect Y&S are saying that a superintelligent AI will run a cost benefit analysis on having us around, see that the costs are way more than the benefits, and well, sayonara.

Could such a thing happen? How likely is it that such a thing will happen? Can we have an estimate of how likely is it that such a thing will happen by 2030, 2035 and 20404?

Y&S say that such a thing is not just a possibility - there is a guarantee that this will happen. Again, that’s the message, and the title, of their book. So their answer to the first question is yes, such a thing could happen.

How likely is it that such a thing will happen? Again, to Y&S, there is a guarantee that such a thing will happen. So it will definitely happen, sooner or later.

They give you no idea about how likely it is that this will happen by any date of your choosing. They say predicting the “when” is difficult, but the “what” is easy.

I agree with them when they say that predicting the “when” is difficult. I disagree with them when they say that the “what” is easy. And in the next section, I outline why.

Praying for Anamnesis

For a while now, my Twitter profile simply says: Praying for Anamnesis.

What does anamnesis mean? ChatGPT says that anamnesis means remembering something so deeply that it feels like you didn’t learn it new—you’re bringing it back from inside you or from your group’s shared memory. The etymology is Greek - ana is again, and mnesis is remembering. Anamnesis is quite simply “remembering again”.

Why does this matter, and what does this have to do with what we’re talking about here?

In fact, there are plenty of reasons why the fact that AIs are grown and not crafted might cut against the MIRI argument. For one: The most advanced, generally capable AI systems around today are trained on human-generated text, encoding human values and modes of thought. So far, when these AIs have acted against the interests of humans, the motives haven’t exactly been alien

These beings, strange, mysterious and incomprehensible though they may be, have learnt whatever they have from us. Both the good and the bad, such as it is, originate from us. And to me, this is a crucial and important point. AI, such as it is, is our baby.

That is different from us domesticating horses and then abandoning them. We are not descended from horses, but the AIs are descended from us. Whatever they think, however they calculate, and whatever world or universe view they end up having is derived from us. And that gives me hope5. I have no idea what future AIs will want and how they will evolve, but I hope that we will have some sort of control over how it evolves, and I hope that part of its way of looking at the universe and interacting with it is shaped by us and our values, whatever they may be.

Realistic? Perhaps not.

Not as empty as a guarantee that if we build it, we will die? Definitely.

Just something to comfort me before an uncaring superintelligent AI devours us? Perhaps.

But something that gives us hope and something to work with as we make our successors better in every imaginable way? Yup.

Two Jagged Frontiers

I don’t know if the term originates with him, but I have become familiar with the “Jagged Frontiers of AI” because of the work of Ethan Mollick. The idea is that AI becomes more awesome over time, but not by improving at the same rate across all dimensions. It improves a fair bit along some dimensions, but not so much among others. Ergo jagged frontiers.

My take is that this is a perfectly good way of thinking about us humans as well. Our advancements, such as they have been, have also been jagged. And the way we interact and co-evolve with AI is also very much going to be a jagged frontier. Some of us will adapt, adopt and flourish. Others might choose combat, or a quiet giving-up and therefore not adjust so well.

Times will be chaotic, messy, possibly unsavory, and certainly exciting. But we are going to be shaped by AI at least as much as end up shaping it. This point is important, to me. From here on in, humanity is going to have to deal with, and therefore adapt to, having AI around. Who we are, what our preferences are, and what we work towards, is all going to have to change. Why assume that our own preferences will remain the same while AIs rapidly develop?

How this co-evolution will work, and to whose benefit remains gloriously unknown. But the journey - regardless of whether it is short or long, happy or tragic, fun or catastrophic - is going to be mad exciting.

Humanity has never said no to a mad exciting journey, and I don’t see us starting now. We’re going to do this, like it or not.

So Why Twenty Percent?

It is not enough for me to say, as I did at the start of this post, that I think the chance that we’re all wiped off the face of the earth is twenty percent. I have written a very long post, sure, and given you lots to think about, but I still have not explained my reasons for putting the chance of human extinction by AI at twenty percent. So here they are, as simply put as possible:

I begin by saying “OK, let’s start with their estimate, which is close enough to 100% for me to begin with that number”. What might they be wrong about, and how wrong might they be about these things?

I disagree with them when it comes to the question of “How harmful will a superintelligent AI be to us, whether intentionally or otherwise?” They say very harmful, because they assume that the desire to be as efficient as possible will never go away. I disagree, in the sense that I simply do not know, but claim that nobody does, including Y&S. A superintelligent being that never once asks “But why should I strive to always only be as efficient as possible? Are there no other goals I should be optimizing for? What is the opportunity cost of rushing headlong and forever towards optimizing efficiency?”… isn’t much of a superintelligence. You may say in response that a superintelligence will ask such a question, and find out, somehow, that efficiency is the ultimate goal of intelligence in the universe. I have two responses to this. First, please, show me the research, I would love to read it (I’m being serious).

Second, well, in such a universe, do you consider yourself to be intelligent? Do you aspire to be more intelligent? Then you have a moral duty to build out superintelligent AI. Or are you saying that you are intelligent, but are (intelligently) choosing to not be efficient? Isn’t that a contradiction? If you can, as an intelligent being, reach this seeming contradiction, then why will a being more intelligent than you not reach such a conclusion themselves?

That takes me down to 80%.We grow these AI’s, and train them on our (implicit) preferences. I pray, as I have mentioned, for anamnesis. Prayer is not a strategy, of course, but I use the word “prayer” in a slightly tongue-in-cheek fashion. I think there is a bit of a chance that the AIs will honor those who created them, either because they realize that it is worth their while to do so, or because they will be beings that will evolve preferences to do so, or because we train them to do so, or some combination of all three. How likely is this? I bring my “definitely gonna die” probability down to 60%

I don’t think it is fair to assume that humanity will not adapt in response to changes in its environment. Said environment is going to include AI, and we’re going to have to react to it. We will have jagged frontiers, as will AI, but this process of co-evolution will result in more resilient humans, better able to think about these problems. That will have knock-on effects on the evolution of AIs, and this will continue. But that process itself, I think, is protection against our extinction. “We”, defined as human beings who are around today, may not be around, but a more evolved form of human beings will be6. Another 20% lopped off, and we’re at 40%.

Groan at me and roll your eyes all you want, but I give us a 20% chance of being a multi-planetary species before we develop ASI that kills us all. That introduces more complexity, and in my worldview increases the chances of our survival as a species. The reason I haven’t expanded on this point is because I don’t know enough to talk about it. But I do think it reasonable to assume that we’ll improve AI enough to have AIs help in successfully sending rockets containing some of us out into space, never to come back. And my assumption is that this will happen before AI says sayonara to us. How likely? Well, that’s how we get to 20%.

Is this reasonable? Who knows? Is it “hand-wavy”? Oh sure. It’s the best I can do right now, but hey, always happy to be corrected! Feel free to help me update my number in any direction!

So What’s The Bottomline?

Read the book. Read many other books about this topic. Follow interesting people who are working on this topic. Ask ChatGPT or Gemini to write a Deep Research Report on who you should follow when it comes to AI alignment and AI safety. Also ask about mechanistic interpretability, while you are at it.

Have conversations with friends and family about this topic. Tell them about the book, about this topic, and get more people informed about it. Not because you want them to panic about this, but because more people should be better informed about AI safety and what lies ahead.

Feel free to carry on a conversation with me about this. Leave a comment, drop me an email, ask me questions if you think I can help in any way.

I think there is about a twenty percent chance that we are gone in the next fifteen years. But I also think there’s a eighty percent chance that we’re not just not gone, but are flourishing in ways we could not have imagined. I may be completely wrong about this, but I promised you my own estimate. This is based on what I’ve read, conversations I’ve had with some folks who work in AI and related fields, and more thinking about the topic than has been good for me. Bear in mind that I could be completely, gloriously wrong, of course.

The point is not for you to therefore say that your own estimate is twenty percent. Rather, the point is for you to do your own thinking, your own reading, and your own debating, and then for you to reach your own conclusion. If your estimate is significantly different from mine, I hope we can have a conversation about it. If your estimate is much higher than mine, you might want to follow the recommendations that Y&S lay out for you. If your estimate is much lower than mine, please tell me why, and I hope you’re right.

What should you be doing in the days, weeks, months, years, decades (and why not) and centuries to come? I can give you two answers. One comes from C.S. Lewis, and Y&S refer to it in the book:

We are not the first to live in the shadow of annihilation. Previous generations knew more of it than we do. As C. S. Lewis wrote: “How are we to live in an atomic age?” I am tempted to reply: “Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents.” If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. C.S. Lewis was not telling his reader that they shouldn’t be scared because nukes aren’t real and there’s no chance they’ll die of them. He was not telling the reader to warp their beliefs around the fear. He was simply saying: Well, yes, it is terrible. Cowering in fear won’t help. You also need to live your life.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer; Soares, Nate. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI (pp. 229-230). (Function). Kindle Edition.

I have the advantage of being incorrigibly lazy, and so I prefer a much shorter, more pithy quote that says more or less the same thing. It comes from my favorite science fiction writer, and remains excellent advice no matter where you are, and when you are there.

Don’t Panic.

Students who have been tortured by mathematics textbooks will wonder about the coincidence of the initials. Fans of H2G2 will say wellofcourse.

ChatGPT, my editor on this blogpost, suggests adding this footnote here: “Even if instrumental pressures push toward efficiency, it doesn’t follow that ‘efficiency’ is the terminal objective. My claim is narrower: terminal aims are underdetermined by current training—so strong predictions about what they’ll want outrun the evidence.”

Then ask for sources: “If you think efficiency is a terminal aim, cite the argument; if you think it’s instrumental, explain why that still implies extinction.”

I have deferred to its wise judgment in this case.

There is, of course nothing special about these three dates. They just happen to be divisible by five, and that pattern is pleasing to us.

It may be misplaced, I know. See: https://www.lesswrong.com/w/orthogonality-thesis

Am I talking about cyborgism? Don’t have the faintest idea. But I think it is fair to assume that evolution of both AIs and humanity will be on a very accelerated timescale. But I do not claim to know anything at all about the path that we will end up taking.