The AI Hayabusa

In yesterday's post, I'd mentioned this:

How long before we abstract away the browser (and the operating system) itself? Can AI not just spin up instantiations of apps, browsers and entire OSes whenever needed, eventually? And this point is important for a reason worth expanding upon in tomorrow’s post, so stay tuned.

A Simple Framework to Think About AI Developments

Long, long ago, back when smartphones didn't exist, I and my then roommate decided to go on a bike ride to Goa. It was an excellent plan (chiefly because it involved Goa), but it had three important drawbacks. First, we decided to ride to Goa in the middle of the monsoon season. Second, we decided to ride there on a Suzuki Max100R. And third, we got lost on the way, and the journey ended up taking far longer than we had anticipated.

Even accounting for all that, it remains one of my favorite bike rides, for many different reasons. But anyways, while chronicling that madcap adventure, I wrote about negotiating a particularly tricky patch of road:

When riding, you're focusing on the road, all the time. You first look up ahead, about twenty meters or so, so you can plan the general direction the bike is going to take. Then you look right in front of you, to avoid the latest potential disaster the road throws up. And you wed the two, and you move on.

Now, if you think about it, this is a good way to think about planning in general. You figure out the general direction you want to head off in, and you need to move in that direction, mota-moti, in the medium to long term. But having decided on that long-term direction, you then need to handle the immediate issues right up ahead (such as a dangerous pothole if you're riding, for example. Or a key employee quitting on you the day after you come up with a long-term strategy. Said strategy, of course, rests upon the skill that only that employee possesses, for another example).

But here's the thing: how far ahead you should look (both in the long term and in the short term), is a function of how fast you are going.

Let's stick with the motorcycle example now. The twenty meters or so rule applies when you are on a Suzuki Max100R, on a mud-track, in the middle of the monsoons. If, on the other hand you are on a Suzuki Hayabusa, on a ridiculously smooth piece of tarmac with excellent driving conditions overhead, you may want to plan with slightly longer distances in mind.

So what's the point?

The point is that with AI, we're on that Hayabusa, even if a lot of us would much rather not be on it. And we're not just on any Hayabusa, this is a Hayabusa that insists on going faster every year. Regardless of the quality of the track, and regardless of overhead conditions, to boot.

And under these conditions, planning only for where the Hayabusa is as of this moment is really bad planning. You have to plan for what lies ahead.

Thinking it Through

If you are a student in a college today, and are graduating over the next (Say) four years or so, you need to be reading (a lot!) about what lies ahead four years from now. Nobody has any concrete answers about what lies ahead four years from now, but a lot of people have a lot of opinions. Those opinions come with narrower confidence intervals for what lies ahead in the nearer future, but that's about the only good news. But hey, as the rider on that ever-accelerating Hayabusa, what choice have you got? Read more about what lies ahead, and try and figure out what you should be doing. Here's an excellent Twitter thread by Reid Hoffman to get you started.

If you are a young professional just starting off in your career, you need to be reading (a lot!) about what lies ahead four years from now. How should you be thinking about what your job might look like four years from now? If four years and your entire job is too complicated to think about, think about the next twelve months, and think about the five key tasks that you can break your job down into. Which of these tasks is "going to go" in the next twelve months, and with what probability. What does that mean for you? What do you plan to do about it?

If you are a businessperson today, hoping to get a product out in the world for other people to buy, how valuable is your product going to be given AI advances over the next three to four years? What pricing power do you see your product having over those three to four years, and how much higher is your estimate than INR 2,000/-? That is, which aspects of your product offerings are "going to go" in that time-frame, what does that mean for you, and what do you plan to do about it?

If you are a teacher (or a professor) today, what do you plan to teach three years from now? How do you plan to teach it, and how do you plan to stay relevant in the classroom? That is, which of the tasks you currently do as a teacher are "going to go" in that time-frame, what does that mean for you, and what do you plan to do about it?

Lawyers, doctors, software engineers, it doesn't matter. We are all on that Hayabusa, and we're all accelerating ever faster. How far ahead are you looking, and what is your plan?

Let's Stare At Charts

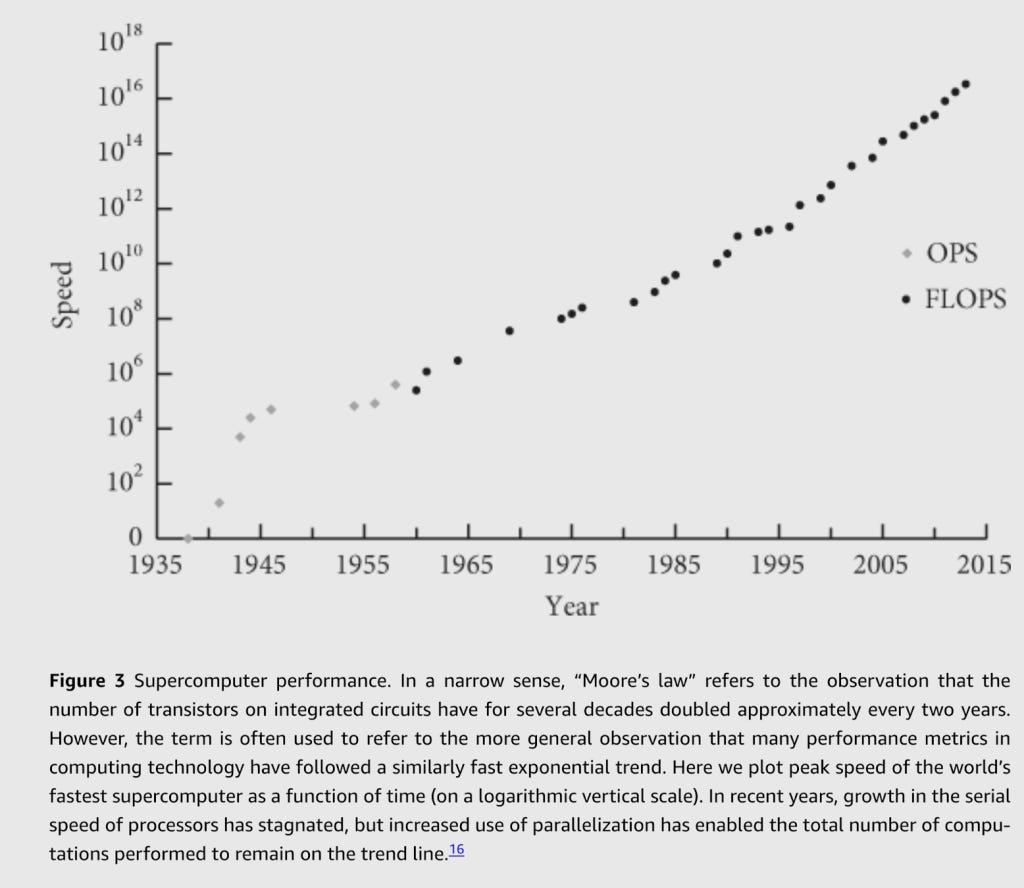

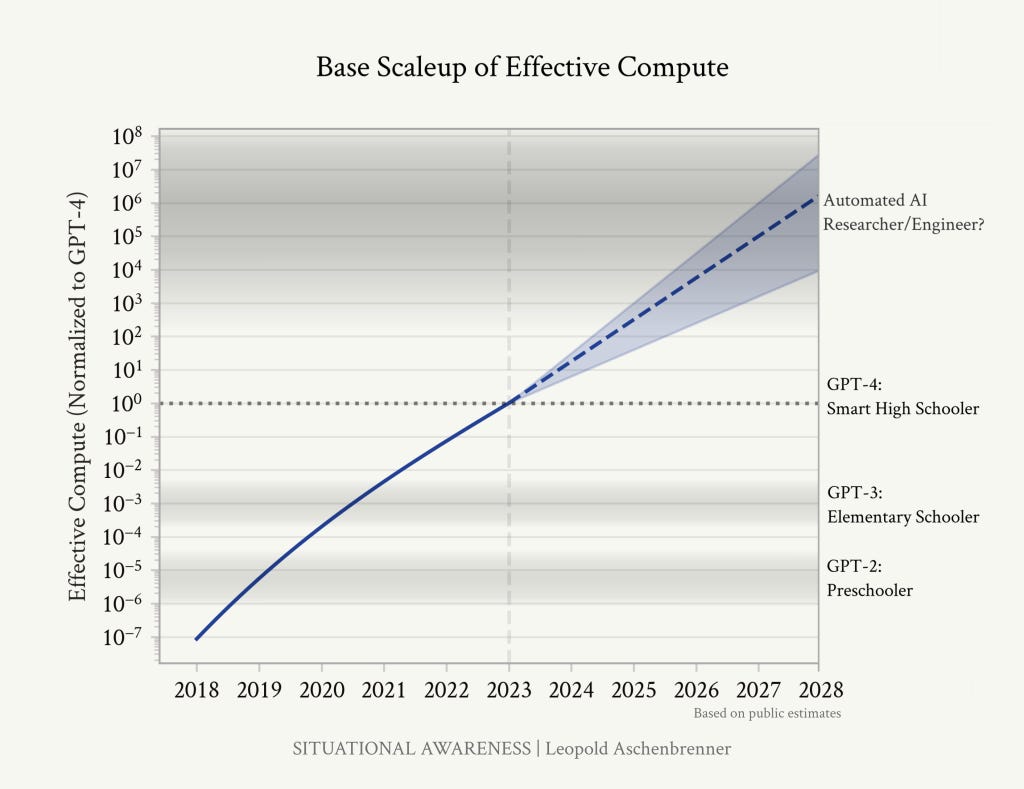

Here are two images for your viewing pleasure:

And here's the second:

The question to ask with both of these trends is the same one: how likely is that the trend will continue? Construct confidence intervals around your estimate, of course, but no matter what your estimate of the trend is, and no matter what your confidence interval is, do ask yourself how far ahead you are looking in your field of work or study, and do ask yourself what you are planning to do about your estimate of the trend.

To Main Kya Karoon?

The bottom line (and my reason for writing this post) is quite literally to ask you to think more about AI, but from a forward-looking perspective.

Do not base your opinion of AI on technologies that were available last year (or even worse, technologies available in 2023 or the years before that). Hell, models that were released last month are already outdated, and by significant margins.

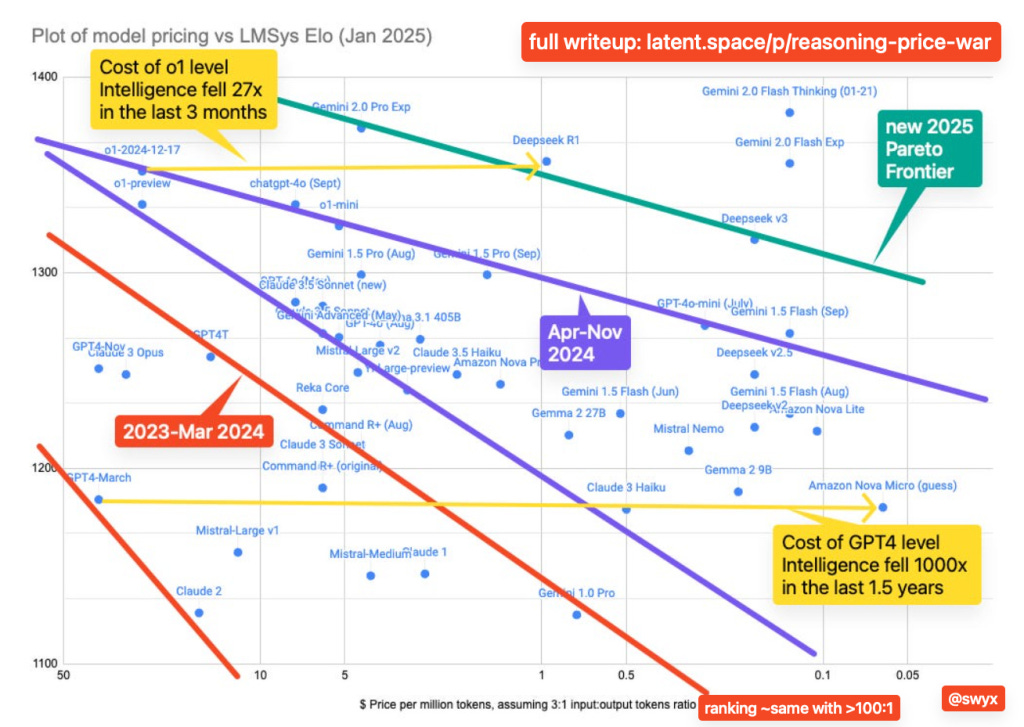

Here, take a look at another chart:

The horizontal axis shows you price per million tokens, but the price gets cheaper as you move from left to right. The vertical axis shows you performance capabilities, as measured on LMSys Elo. Higher is better.

The red, purple and green lines show you the Pareto frontier - think of it as the trade-off between price and performance. The red line, for example, shows you that a 200 point Elo drop in also resulted in your price for that performance falling from $50 per million tokens to about $0.5 per million tokens.

The green line, on the other hand, was for 2025. The green line being flatter means that you don't have to give up that much performance for much cheaper pricing. The "strictly-ok" models in 2025 gave you much better performance than the "strictly-ok" models in March 2024, and for a much cheaper price.

And the fact that the green line was above the red line throughout means that all models in early 2025 were better than all models in March 2024. Nobody uses Gemini 2.0 anymore if they want to use cutting-edge models, they use Gemini 2.5.

And finally, note that I used the past tense while talking about the 2025 line.

Gemini 2.5, which is so new that it wasn't even on that chart, has been updated thrice since launch. And it will be updated again today.

That chart was made in January of this year, and it is already hopelessly outdated.

Where is your Hayabusa likely to be by December 2025? What are you planning to do about it?

Where is it likely to be three years from now? What are you planning to do about it?