Learn, Your Way

Steam-powered manufacturing had linked an entire production line to a single huge steam engine. As a result, factories were stacked on many floors around the central engine, with drive belts all running at the same speed. The flow of work around the factory was governed by the need to put certain machines close to the steam engine, rather than the logic of moving the product from one machine to the next. When electric dynamos were first introduced, the steam engine would be ripped out and the dynamo would replace it. Productivity barely improved.

Eventually, businesses figured out that factories could be completely redesigned on a single floor. Production lines were arranged to enable the smooth flow of materials around the factory. Most importantly, each worker could have his or her own little electric motor, starting it or stopping it at will. The improvements weren’t just architectural but social: Once the technology allowed workers to make more decisions, they needed more training and different contracts to encourage them to take responsibility.

I’ve used this excerpt before, and I fully expect to use it again. I love it because of how the second paragraph starts. “Eventually, businesses figured out that the factories could be completely redesigned on a single floor”.

Why did this happen eventually, rather than immediately?

Because given an improvement in technology, it is easier and more natural to ask how said technology can help improve existing workflows. It is much more difficult, unnatural and counterintuitive to ask how said technology can help in coming up with new workflows. And it is all but impossible to even think through the implications of realizing that you may end up hindering the optimal development and deployment of new workflows by simply trying to help - so we won’t go there today.

But we have been exploring over the past few posts how to think about a reimagined classroom experience, so let’s continue with that theme.

Learn Your Way

I love the subtle little pun in the title, but that’s not the only reason to love Google’s latest initiative in the education space. It’s called Learn Your Way.

Textbooks are a cornerstone of education, but they have a fundamental limitation: they are a one-size-fits-all medium. The manual creation of textbooks demands significant human effort, and as a result they lack alternative perspectives, multiple formats and tailored variations that can make learning more effective and engaging. At Google, we’re exploring how we can use generative AI (GenAI) to automatically generate alternative representations or personalized examples, while preserving the integrity of the source material. What if students had the power to shape their own learning journey, exploring materials using various formats that fit their evolving needs? What if we could reimagine the textbook to be as unique as every learner?

That’s an excerpt from a blog post that serves as an introduction to the product, written by Gal Elidan and Yael Haramaty.

And the obvious thing to realize once you read this is that it is only a matter of time before the last question in that excerpt is asked of everything in education, not just textbooks.

Here’s why:

When you live in a world where entities that know a subject well (and can explain that subject well!) are scarce, you arrange learning around that scarce resource. A classroom as we know it isn’t the optimum way to learn for all times. It was the optimum way to learn given the fact that good teachers were in scarce supply. But when this is no longer the case, why insist on having learning happen in conventional classrooms? Run experiments, collect the data, and if you see that there are better ways to learn, go ahead and use ‘em!

See if you can apply this same logic, but to textbooks instead. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Here’s my attempt:

When you live in a world where it is expensive to produce good quality textbooks that are customized in terms of content, flow, explanation styles and problem sets, you arrange learning around the few well written textbooks that are available to you. But a textbook as we know it isn’t the optimum way to learn for all times. It was the optimum way to learn given the fact that good textbooks were in scarce supply. But when this is no longer the case, why insist on having learning happen via conventional textbooks? Run experiments, collect the data, and if you see that there are better ways to learn, go ahead and use ‘em!

Same paragraph, as you have no doubt noticed, and of course it was intentional. That is my point in this blog post - to show you that it is inevitable that what is happening to textbooks today will happen to classrooms tomorrow, semesters the day after, and degrees after that. OK, I’m being rhetorical about the timelines, but I’m willing to take a bet on the direction I’m outlining here, sure.

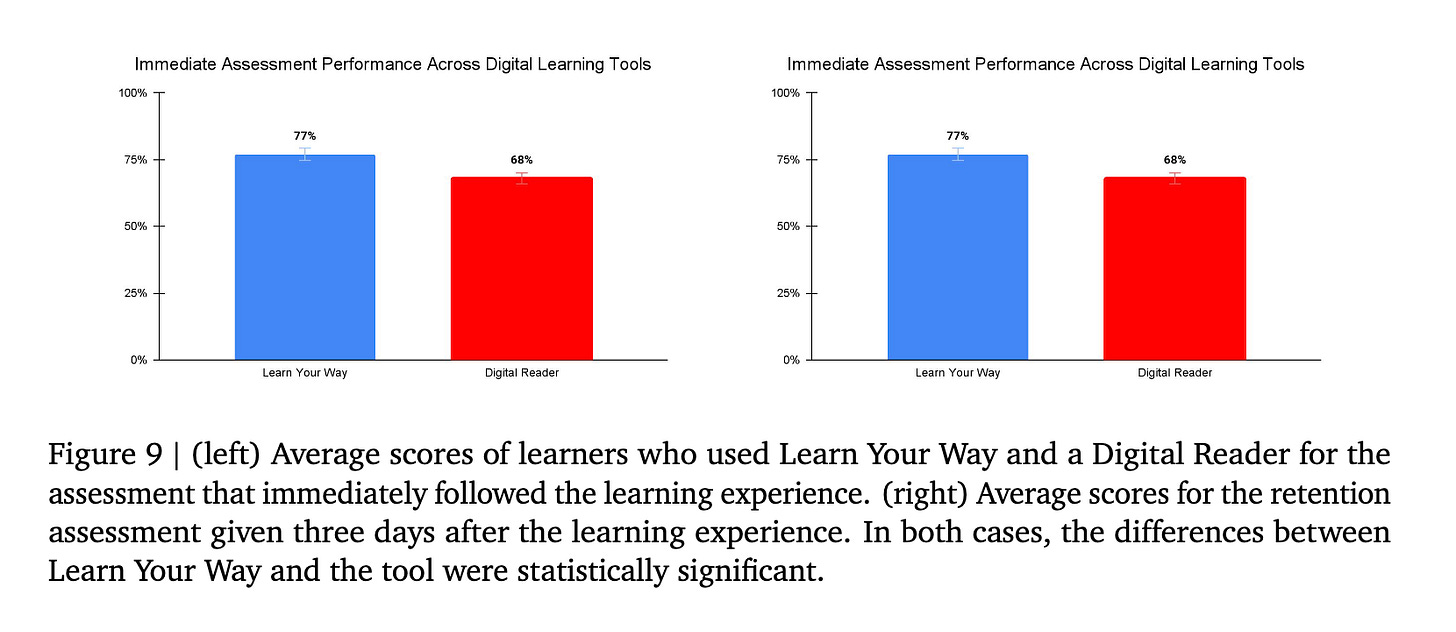

There is one important difference between the two paragraphs, though. Learn Your Way has run some tests, and they have early results:

Over the next year, keep an eye out for more such experiments. These experiments will come for more components of our current educational setup.

Eventually, businesses will figure out that learning can and should be designed around a single learner.

Context Is That Which Is Scarce

This does not reduce the importance of campuses. On the contrary, it makes them more valuable. Sure, it reduces the importance of the way we organize classrooms currently. But in-person learning, in-person interactions on campus, and in-person mentoring goes up in value in such a world, not down.

We still will need to discuss what we’ve learnt, explore how other people are applying what they’re learning, and just socialize. This is true for all of us, but especially young folks.

So if you think that campuses are going to go away in the post-AI age, I disagree with you. But hey: if you think that classrooms are not going to go away in the post-AI age, I disagree with you even more.

But the way we learn and teach is going to change in front of us, and it will happen very, very soon. Buckle up, we have exciting times ahead of us.